Special City Report: Pereira, Colombia – Sponsored by: World Trade Center Pereira

Hospitality, an upgraded airport, and a World Trade Center help boost this Colombian city

By Doreen Hemlock / Photos by Rodolfo Benitez

PEREIRA, Colombia. It’s a weekday morning in this small, welcoming city in Colombia’s coffee-growing heartland, and residents of mountainside neighborhoods are commuting comfortably through the air on Alpine-style cable cars, riding high above the streets, looking down on lush, green parks.

The modern transit system is one sign of the rise of Pereira, a metro area that surveys call Colombia’s most livable, with low unemployment and growing foreign investment, some from Miami.

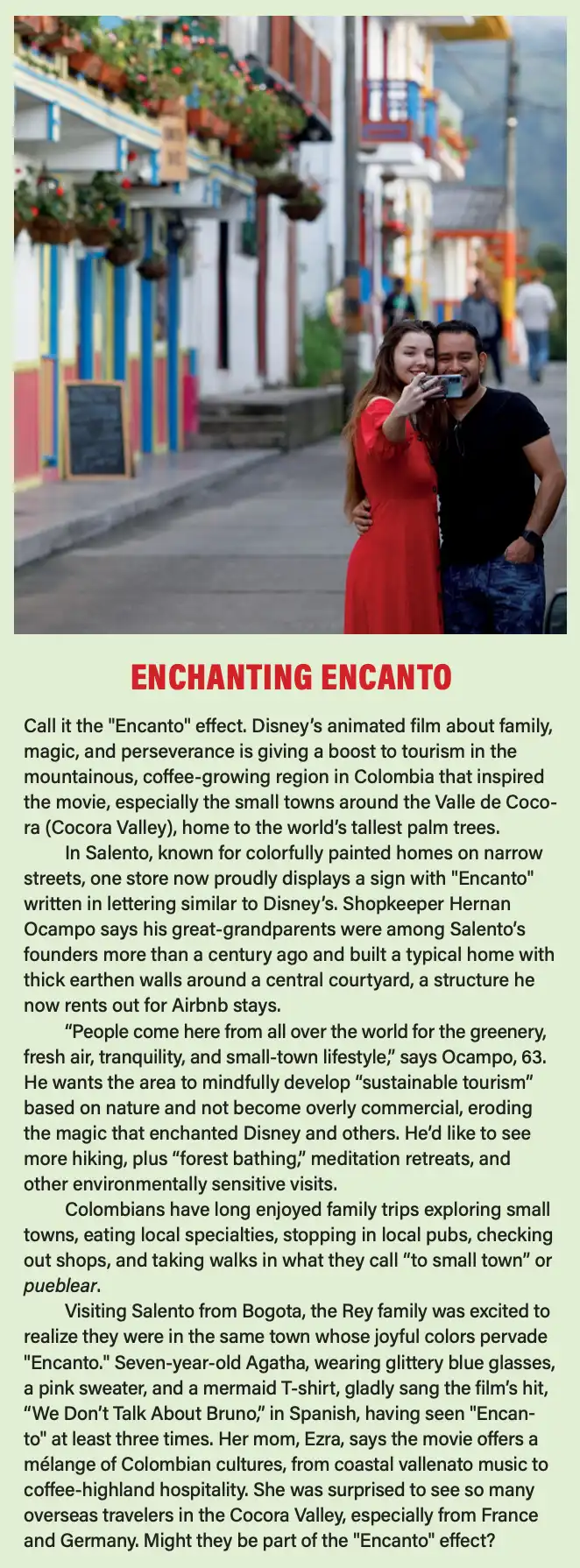

Pereira shines as the hub of the region that inspired Disney’s film “Encanto,” with its charming towns, open-hearted people, and the world’s tallest palm trees. Deemed a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its “coffee cultural landscape,” it made Forbes’ list of the best places to visit this year and the Bloomberg Pursuits list last year. It’s already a top tourism destination for Colombians.

Long a center for apparel and local commerce, Pereira is now diversifying in manufacturing and becoming a distribution center for the coffee zone and beyond. With pro-business leaders, an upgraded airport, and improving highway links, it’s attracting foreign investors too. A Cuban-American entrepreneur is launching a Pereira-based airline, Aerolineas del Café, which will fly to Miami and such Caribbean tourism spots as Punta Cana. And a group from South Florida is setting up the new World Trade Center-Pereira, complete with a tower to feature corporate offices, apartments, and medical tourism facilities. Pereira leaders now promote the area for business in Miami-Dade County, officially their “sister” metro.

The city’s rise began at least a decade ago, but COVID-19 sped growth. Lots of tech-savvy entrepreneurs began moving to the area from bigger Colombian cities for better quality of life and lower costs, much like New Yorkers have flocked to Miami. Even some Americans are retiring in the region to enjoy year-round weather in the 70s Fahrenheit, friendly folks, and prices a fraction of those in Florida.

One newcomer from Bogota, business consultant Juan Jose Lopez, says the region’s collaborative culture has transformed him. “In Pereira,” says Lopez, speaking Spanish, “I’ve learned to change one letter: from yo (meaning “I”) to co-,” as in community and co-create. His work is more group-focused.

Here are five aspects of the rise of Pereira, a metro area of some 700,000 residents that some compare to a Boca Raton or Kansas City in the U.S, or a mini-Medellin in Colombia, especially now that the city hosts the same aerial cable car system that helped usher in the “Medellin Miracle.”

A MODERN AIRPORT: A 3.5-HOUR FLIGHT FROM MIAMI

Fly direct from Miami to Pereira on a flight that takes about 3.5 hours, and the first thing you notice is the bright, new airport terminal. Colombia’s Avianca Airlines has long served the destination from Miami, and American Airlines began direct Miami-Pereira service five years ago, even before the $60 million airport upgrade that added the terminal and extended the runway for larger jets.

Business has jumped at Pereira’s Matecaña International Airport since that 2020 renovation. Last year, nearly 3 million passengers flew in and out, about double the 2016 tally, says airport manager Francisco Valencia, a 43-year-old lawyer long active in Pereira affairs. Plans call for growth to 5 million passengers yearly in the 2040s, but, says Valencia, “we’ll reach that number earlier, for sure.”

Built in the 1940s by Pereira residents, picks and shovels in hand, Matecaña is city-owned. Yet the airport is privately run in one of the public-private partnerships now popular in Colombia. The operator, part of CSS Construction, also runs Bogota’s new El Dorado airport and some dozen others in Latin America, says Jorge Diaz, the Chile-born airport operations manager. Diaz also expects strong growth at Matecaña, partly because outmigration from the coffee zone in the 1990s and 2000s – after a major earthquake and the Great Recession – keeps fueling demand for flights back to visit family.

“That painful emigration gives us a more global and cosmopolitan view here,” says Diaz, predicting direct flights year-round from Matecaña to New York and Madrid some day.

Miami entrepreneur Tony Guerra sees so much potential that he’s starting a new airline in Pereira, Aerolineas del Café. He expects to launch three-times-a-week charters to Miami soon and then begin scheduled services to Miami and such Caribbean tourist havens as Punta Cana and Cancun. He has long operated charters between Miami and Cuba, popular among travelers who carry lots of luggage.

Guerra says he’s amazed that experienced aviation staff in the city were able to obtain approvals for his new carrier within months, faster and at a lower cost than in Miami. “When people share my passions and dreams,” says Guerra, “I know I’ve found the right team.”

From Matecaña, varied airlines now offer year-round flights direct to such Colombian cities as Bogota, Medellin, and Cartagena, and overseas to Panama and Miami. Colombia’s Avianca began seasonal service in December to New York and Miami. The airport’s VIP lounge debuted in September.

LOGISTICS EXPANSION: FOR THE COFFEE ZONE AND ALL COLOMBIA

Visit the warehouses and logistics parks filling up on Pereira’s outskirts, and you also feel the area modernizing. Businesses mainly distribute goods for the coffee region, and some serve the entire country, an area nearly twice the size of Texas and home to 51 million residents.

Juan Martin Noreña, shown above, general manager of the Coffee Zone Logistics Center, sees Pereira as a perfect nationwide hub for a simple reason: location. The city sits in the center of a circle that has, within a 120-mile radius, all three of Colombia’s biggest cities – Bogota, Medellin, and Cali – and the country’s busiest Pacific coast seaport, Buenaventura. That circle represents nearly half of Colombia’s population and more than 75 percent of the country’s economic output, Noreña says.

“Our biggest challenge has been the mountains, which traditionally fragmented our country and made road transport difficult,” says Noreña. “But with new highway systems being built under private concessions, and Bogota so crowded and running out of space for warehouses, we see opportunities for Pereira to increasingly become a distribution center for all of Colombia.”

Costs are part of the draw. Rental rates for warehouse space at Pereira area logistics centers now run under $1 per square foot, slightly less than Bogata and cheaper than Medellin, according to reports from commercial real estate brokers. Also alluring: room to grow. Unlike Bogota, Pereira has ample acreage to develop big warehouses, says Noreña.

Among companies selling nationwide from Pereira is locally based Duna, which distributes motorcycle parts, mainly from China, and employs 55 people. Finance manager John Castaño lauds the area’s “strategic location” and its proximity to Buenaventura, where the motorcycle parts arrive by ship.

Today, most logistics in Pereira remain regional. Germany-based DHL Express, for example, centralizes its fast-turn, air-cargo deliveries in Bogota and then sends goods onward, says Colombia country manager Allan Cornejo. Even so, DHL Express plans to add a third sales office in Pereira this year to handle the area’s rising volumes of air freight, such as specialty coffees and spare parts for factories. Says Cornejo, “The coffee region is becoming an important development hub for the country.”

WORLD TRADE CENTER-PEREIRA: AN ICONIC TOWER RISING

Tech entrepreneur Jacob William took a circuitous route from India through the U.S. to invest in the World Trade Center-Pereira and its signature tower, soon to rise next to the city’s convention center.

William had built up an outsourcing company, Flatworld Solutions, that grew to more than 5,000 employees in call centers and back-office services worldwide, including some in the Philippines and Latin America. While doing business in Bogota some six years ago, he visited Pereira and was captivated by the area’s generous people, hearty meals like pork chicharron, and mountains like those in his native Tamil Nadu in south India. He found the region business-friendly and poised for robust growth, its tech universities a helpful component. He sensed the city was “like what Austin was many, many years ago.”

Long familiar with the World Trade Center (WTC) network, William opted to buy the WTC license for Pereira to take part in that growth. He teamed with fellow South Florida resident and colleague Lauro Bianda, who also grew up around mountains in his native Switzerland. As co-founders, they foresaw the WTC-Pereira hosting many outsourcing firms and even offering tech courses to students from across Latin America.

“I truly believe that training, education, and technology are what [will] bring Latin America to its potential,” says William. “And the World Trade Center brand will be a beacon for Pereira on the world map,” integrating the city into a network of more than 300 properties licensed in some 90 countries.

The WTC-Pereira tower aims to be iconic in itself, designed by world-class architects and marketed by the Colombian unit of Colliers International, the global real estate firm based in Canada.

Colliers already has sold most of the apartments in the 14-story tower, units that can be rented out for Airbnb-type stays. It’s now selling the tower’s retail space, offices, and medical facilities, tapping the trend of U.S. residents and others to visit Colombia for affordable healthcare from dentistry to anti-aging treatments. Plans call for glass elevators to highlight mountain views and electric-vehicle chargers, among other eco-friendly features, says Colliers development director Cesar Cano, who hails from Guatemala.

“An Indian, Swiss, and Guatemalan doing a project in Pereira is something I’d never imagined,” he joked. The WTC tower, just a short drive from Matecaña airport, is due for completion in late 2025. Bianda says the WTC team appreciates Pereira for its big-heartedness. An example: One night talking in the hotel lobby, William realized he’d forgotten to bring dress shoes he needed for a meeting the next morning. Bianda asked a hotel employee if stores were open, but she said it was too late, asking why he needed shoes. A short while later, the employee returned with dress shoes she’d fetched from her home – new ones her husband hadn’t worn yet. She said to keep them and hoped they’d fit. They did.

“It was beyond kindness and generosity,” says Bianda. “And that’s what keeps surprising me about Pereira: the people.”

PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIPS: TAX BREAKS, OPPORTUNITIES

Government and civic groups play a key role in any community, and in Pereira, they’re united in promoting the city, infrastructure, and jobs. Mayor Carlos Maya, elected in 2020, works closely with the Pereira Chamber of Commerce and spoke with Global Miami at its offices. He’s been prioritizing the economy and education, even personally earning an online master’s degree in “smart cities.”

Under Maya’s helm, Pereira became the first city in Colombia to open after COVID-19 lockdowns. “We had to deal with problems of public health and economic health at the same time, not consecutively, or too many businesses would have gone bust,” says Maya, 43, a longtime accountant with the municipality. Pereira offered vaccines widely, even in its soccer stadium. It also boosted tax breaks for companies creating jobs, with rates falling to zero percent when firms added at least 100 new positions.

That unified approach has helped the city excel, with the lowest unemployment rate among cities in Colombia (8.6 percent in January), the lowest inequality score nationwide (a Gini co-efficient of .4 in 2022) and an improved municipal credit rating (AAA from Fitch in August), surveys show. “City coffers now take in more tax revenue than they did before COVID,” thanks to added business, says Maya.

In recent years, Pereira has been welcoming new call centers, agribusiness, factories, retail stores, and hotels, with a Hilton soon to open. Investors often find the customer service better, staff turnover lower, and costs more modest than in bigger Colombian cities, says Chamber President Jorge Ivan Ramirez.

“Your dollar really stretches here,” says Andrea Salazar, who runs the Chamber’s Invest in Pereira program. Colombia’s minimum wage now runs about $300 a month at March 2023 exchange rates. In Pereira, an employee earning $1,000 monthly and manager $2,000 monthly earn good salaries, she says. A family of four can live well on $5,000 monthly, with children in private school, household help, and a country club membership – a lifestyle impossible with that income in Miami or even in Bogota, says Salazar, who left Colombia’s capital and jobs at multinationals during the 2010s to return and give back to the coffee region where she grew up.

Of course, faster growth and in-migration bring challenges too, as longtime Floridians can attest. “One thing I worry about is losing our culture: the way we help others, say hello, and welcome everyone. We stop at an intersection and let someone pass,” says the Chamber’s Ramirez. “We joke now, when we hear someone honk their horn, ‘Oh, they must not be from here.’ I was taught to only honk in an emergency.”

AERIAL CABLE CAR: A SYMBOL OF PEREIRA’S ASCENT

Perhaps the clearest sign of Pereira’s rise is its new aerial cable car, known as MegaCable, which links hillside communities with the downtown, slashing transit times and opening new opportunities for jobs, education, and other activities.

Colombia pioneered the use of Alpine ski-lifts for public transport in the early 2000s in Medellin in a “social urbanism” project that helped usher in what’s called the “Medellin Miracle.” By boosting access for the poorest residents and better integrating them into the mainstream, crime and poverty plunged. The transit system worked so well that it’s since been deployed in many Colombian cities and across Latin America, including in Mexico, Ecuador, Bolivia, and the Dominican Republic, says project advisor Juan Pablo Lopez.

Pereira opened its aerial cable car system, Colombia’s longest at 2.1 miles, in September 2021. Now, residents of the low-income, hill-top Villa Santana neighborhood can reach the downtown in comfort on a single fare in 14 minutes, instead of paying at least two fares on separate, crowded road trips that often take an hour or more. Plus, they can access the city’s MegaBus system on that same fare.

“The role of public transit in economic development can be quite intangible, but it’s important,” says Lopez, 35, who works on cable car projects internationally. “It improves the quality of life. You can have more hobbies, more time with the family, and not spend all your time going to work and back.”

Pereira’s MegaCable now averages some 8,000 riders per day, reducing vehicular traffic and pollution. Construction took about 21 months, less time with less disruption than light-rail or subway, he says. “Development costs for aerial cable cars are about 10 percent of the price for a subway,” says Lopez. “And the space you need for cable car towers is relatively small, like placing needles in urban acupuncture.” The cable system is such a source of pride that coffee zone families often ride it for fun to enjoy the lofty views and sensation of flying. Some elders who’ve never boarded a plane have cried on the ride.

Managers of MegaCable personify how far Pereira has advanced. Many are sons of farmers, the first in their families to finish college. Lopez’s dad worked with farm animals, then for the city, and in his 40s, graduated as an economist. He encouraged

his children to study and attend college, “preferably a public one.” Lopez earned his engineering degree at Pereira’s public research Tech University, where he first worked on maintenance software for a cable car system. “That’s the story of all of us,” he says.

Ramirez can relate. He’s the son of coffee farmers and put himself through law school, working and studying full-time. At 43, he warmly helps the community keep banding together to modernize, and, more and more, to tap international tourism, investment, and opportunities.

“Pereira,” says Ramirez humbly, “is a city that’s discovering the world, and the world is discovering.”