Colombia’s “Golden Gate” beckons for business with U.S. nearshoring, call centers and investment

Barranquilla, Colombia – This tropical city off the Caribbean coast is best known overseas for its cultural and sports treasures: its festive Carnival, singer Shakira, actress Sofia Vergara, fashion designer Silvia Tcherassi, and baseball great Edgar Renteria, to name a few.

Now, the port city is building a reputation as a hub for “nearshoring,” both in manufacturing for U.S. sales and in call centers for U.S. clients. It’s also emerging as a model for sustainability. Its public parks program just won a global prize, chosen among entries from 155 cities. And it’s the first district in Colombia rolling out English studies in all public middle-and high-schools, aiming to ensure the language skills for long-term business with its top trade partner, the United States.

Colombia’s fourth largest metro area by population, Barranquilla is leveraging its location as the country’s big city closest to the U.S. It’s just 2.5 hours by air from Miami, a flight shorter than the Miami-New York route. Executives from Florida can fly in and out the same day. And Barranquilla is just three to four days by ship from South Florida, with freight costs now as low as $1,600 for a 40-foot container, cheaper than many transits within Colombia or within the U.S. itself.

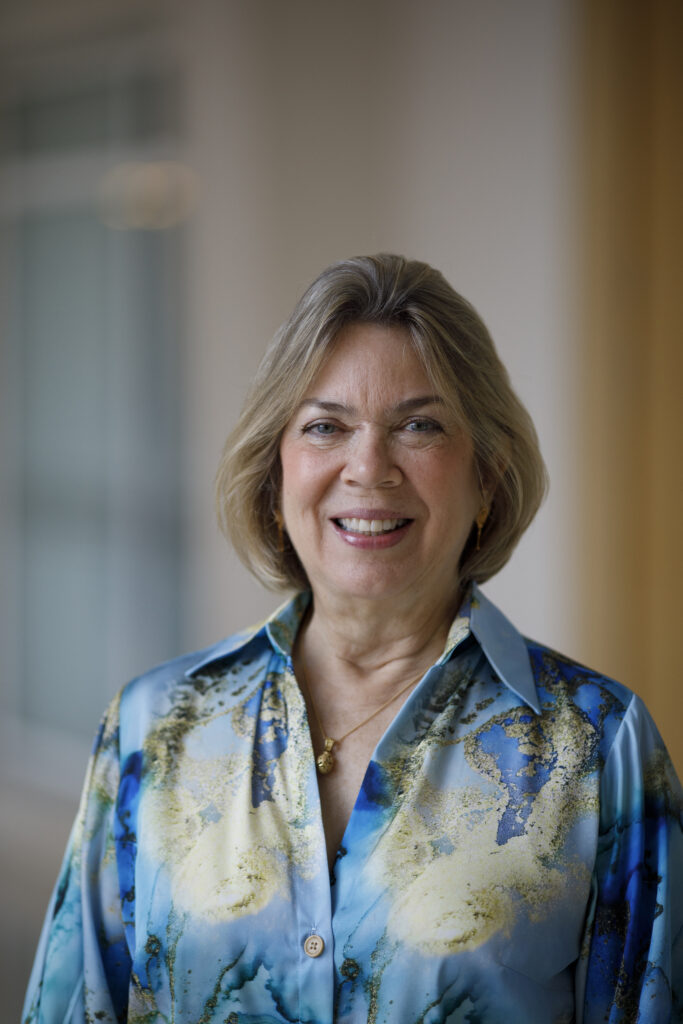

“Our orientation as a port city is international. We see the United States as our natural partner and Florida as our primary gateway to the U.S.,” says Vicky Ibañez, executive director of the American Chamber of Commerce in Barranquilla, the largest AmCham chapter in Colombia relative to city size.

Chamber of Commerce in Barranquilla

BUILDING ON ITS HISTORY AS COLOMBIA’S “GOLDEN GATE”

Barranquilla’s location by the Caribbean and proximity to Florida has long been key to its development. In the early 1900s, especially around World War II, its seaport welcomed diverse immigrants, including Jews from Europe plus Middle Easterners, both Christian and Muslim. That influx prompted its nickname “Colombia’s Golden Gate” and explains why Middle Eastern food now is considered “local” cuisine.

The city also was the launchpad for Colombian aviation. The airline that became Avianca, Colombia’s flag carrier, began in Barranquilla in 1919, making it the world’s second oldest after the Netherlands’ KLM. Initial flights from the airport, named Ernesto Cortissoz for an Avianca president, headed to South Florida.

When Colombia started free trade-zones to encourage exports, Barranquilla opened the first one – back in 1958. That zone now hosts some 70 companies, most selling to the U.S.

Still, it’s only been in the past 16 years that Barranquilla has shaken off its late 20th-century doldrums to again shine among Colombia’s dynamos. The spark came from a group of visionary mayors led by Alex Char, the son of a wealthy family that owns Colombia’s Olimpica supermarkets and other businesses. Char was elected in 2007, pledging to forge a public-private partnership and tackle such pressing problems as severe flooding after rains. He delivered, even installing underground pipes to channel rainwater. Barred from consecutive terms, he was re-elected in 2015 and just won re-election for another four-year term starting in January. Peers from his group have won in between, providing continuity in policy and laying out a city plan through 2100, with an emphasis on international business.

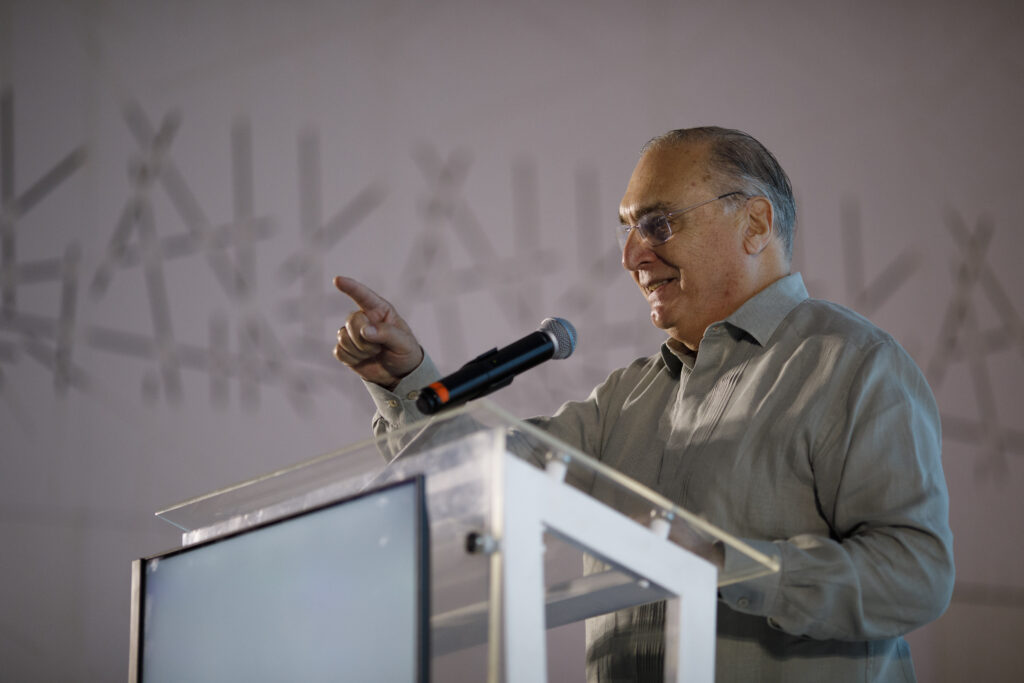

President & CEO at Atlantic Quantum Innovation

“The most important change in these 16 years is our mentality. Now, we think big and long-term,” says Lelio Sotomonte, who runs the city’s biggest call center, Atlantic Quantum Innovation, which serves many U.S. clients. “We’re reclaiming our role as Colombia’s Golden Gate.”

TECNOGLASS: BARRANQUILLA’S LARGEST MANUFACTURER

The clearest example of Barranquilla’s near-shoring success comes from Tecnoglass, a company founded by a family of Middle Eastern heritage. It is now listed on the New York Stock Exchange and soon to reach $1 billion in annual sales. Tecnoglass makes specialty windows used in numerous high-rises across Florida and the U.S., including Miami’s Brickell City Centre and its One Thousand Museum tower.

Tecnoglass started out in 1983 making solar water heaters for Colombian homes but pivoted with changing market conditions. In the 1990s, it began exporting specialty glass to Miami, and in the 2000s, started selling its specialty windows in South Florida. In the 2010s, it listed its stock on Wall Street, first on the Nasdaq exchange. Last year, it posted sales topping $716 million, almost all in the U.S., from Miami to Chicago and as far west as San Francisco, says chief operating officer Christian Daes.

“We went public on Wall Street not for money, but for credibility. Outside Miami, when we’d say we’re from Colombia, we’d often get questions like: ‘Where is Colombia? What can I do if there’s no delivery?’” Daes says. “After listing, we could say, ‘Look at our stock ticker and reports. We’re for real.’ “

Tecnoglass now employs more than 9,000 people in Barranquilla, making up to 3,000 custom windows daily and even mobilizing robots for inventory control. To keep exports growing, the company just moved its global headquarters to Miami. Daes commutes regularly from Florida to the Barranquilla factories, as he also develops a large Miami area showroom to serve their U.S. clients.

Beyond exports, Tecnoglass stands out in Barranquilla for the city monuments that it has donated and maintains. In the past five years, it’s unveiled the colorful Ventana Al Mundo (Window to the World), often shown on TV as the city’s icon and rising some 15 stories; and Ventana de Campeones (Window of Champions), a landmark often called “Shark Fin” that stands about 10-floors high.

Daes calls the landmarks part of his company’s “social responsibility,” which also features college scholarships for employees and their families, on-site health clinics and sports facilities at factories, wheelchair donations, and strong participation in the Barranquilla Carnival, among other programs.

“What’s most important is people,” says Daes, whose family immigrated to Colombia a century ago seeking opportunity. “Everyone in Tecnoglass has my personal phone number and email.”

ASSETS FOR NEAR-SHORING: FREE-TRADE ZONES, SEAPORTS, AIRPORTS

Located on the lowlands of the Magdalena River some 15 miles inland from the Caribbean Sea, Barranquilla touts more than proximity to the U.S. to attract nearshoring. Its four free-trade zones also offer tax breaks and other incentives for exporters. Hundreds of companies now operate in the zones, making everything from shampoo to scaffolding, mainly for U.S. buyers. Some, such as outdoor furniture maker Kannoa, have relocated production from distant China.

Costs are part of the lure. At today’s exchange rates, Colombia’s minimum wage runs about $300 per month, slightly less than Mexico’s and about a third of Costa Rica’s, says Manuel Herrera, general manager of the Cayena Free Zone, the busiest zone in Barranquilla. Cayena now hosts tenants that directly employ about 3,000 people, double the number two years ago, Herrera says.

Since the COVID pandemic, businesses are looking more at “quality-of-life” issues for managers and staff, and Barranquilla is gaining there too, says Marcela Barrios, vice president of the Barranquilla Free Zone, the city’s first zone and the only one with its own seaport. The metro area of some 2 million residents now offers a miles-long riverwalk, a mangrove eco-park, award-winning restaurants, and more international schools.

“Nearshoring is not just for companies, but for the people who come to do business here,” says Barrios. “We’re a city with Germans, Americans, Middle Easterners, and a multiplicity of cultures and cuisines that makes newcomers feel welcome.”

Also vital for nearshoring: strong sea and air links. Barranquilla’s main seaport has been diversifying its services and investing to grow. Since 2021, the Port of Barranquilla has been owned by Miami-based infrastructure fund iSquare Capital, which has helped update operations, trim costs, and reduce accidents, says chief operating officer Aldo Signorelli. The seaport now offers most forms digitally so that users can pay bills online and track cargo status in real time. Last year, the port’s terminal handled some 5 million tons of freight, from containers to liquids and breakbulk, to place among Colombia’s five busiest. Service to South Florida came from at least two Miami-based lines, Seaboard Marine and King Ocean.

The seaport is expanding into logistics services too. It now offers a large, refrigerated warehouse for perishable and frozen goods, which handles exports of avocados, blueberries, and frozen fruits and vegetables for the U.S. and other nations. Plus, there’s space for more projects on its sprawling acreage, says Rene Puche, the seaport chief for 10 years. He left a career with a Norwegian fertilizer company, which included years in Europe and Africa, to return to his hometown and lead the port, encouraged by the city’s turnaround and its growing collaboration with business. “There’s an honest and open dialogue between the private sector and government on ways to foster long-term growth and sustainable development,” says Puche.

Barranquilla’s airport also is becoming more international in focus. Besides flights to many Colombian cities, it now serves some half-dozen destinations overseas in the U.S., Panama, Dominican Republic, and the Dutch Caribbean islands. American Airlines flies daily from Miami and Spirit Airlines daily from Fort Lauderdale. Colombia’s Avianca also flies from the city to Miami several times a week, says Marcel Di Muzio, the marketing manager with the airport’s private operator.

The airport handled a record 3.1 million passengers in 2022, up from 2.8 million in 2019, as more visitors came to Barranquilla for business travel, Carnival festivities, and increasingly, for medical tourism at the city’s abundant eye-care and dental clinics, says Di Muzio. He sees room for growth not only for passengers and cargo but also for refueling and maintenance. The airport has a lengthy runway – about 10,000 feet long – that already serves as a landing strip for U.S. Air Force jets on maneuvers over Colombia.

“We can land the world’s largest planes like the A380 with no problem, and being at sea level, can become a hub for refueling too,” the trilingual di Muzio told Global Miami Magazine.

TOUTING FUTURE OPPORTUNITIES

To spread the word about its offerings, Barranquilla is turning to conventions, some at its newly built, riverfront Puerta de Oro Convention Center, touted to hold up to 16,000 people cocktail-style.

The city recently beat out larger rivals to host the Latin American convention of the American Association of Port Authorities (AAPA). The Dec. 4-6 event is set draw some 1,000 ports leaders, users, and suppliers from dozens of countries to the center, both for talks and for city tours.

Port leaders see the timing as especially propitious. Seaports near the U.S. now have an edge in the transport of goods to U.S. buyers: Ocean shipping averts the serious congestion and delays facing trucks crossing the U.S.-Mexico land border, making water transit generally faster, less costly, and more environmentally sound, says Rafael J. Diaz-Balart, the Cuba-born, Miami-based executive who is AAPA’s coordinator for Latin America.

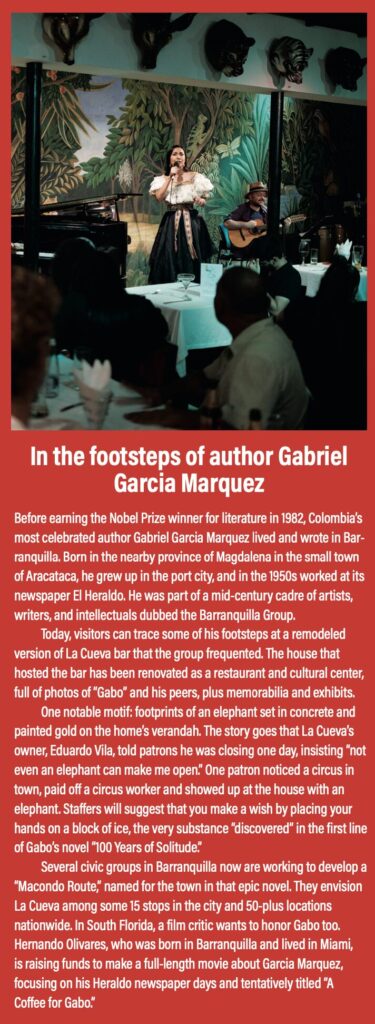

AAPA’s coordinator for Latin America

“Don’t let this moment pass by to take advantage of nearshoring in Colombia,” Diaz-Balart told a meeting in Barranquilla, a city where he says people “embrace visitors like members of your family.”

Going forward, many see opportunity beyond manufacturing– into cleaner energy. Already, the mayor’s office is installing solar panels on government buildings to expand renewables as part of its “BiodiverCity” push. Barranquilla recently teamed with a Danish company to explore development of a 350 MW offshore wind farm that would be Colombia’s first, tapping the area’s strong winds. Plus, the Atlantico Department has potential to develop natural gas reserves offshore that could boost exports, studies show.

“We have everything we need to be an energy hub not only for Colombia but for the world,” says Vicky Osorio, executive director of investment promotion group ProBarranquilla. She envisions the city mobilizing its skills in metal-working to build industrial components for a growing energy sector.

There’s also a push to expand business promotion along Colombia’s entire Caribbean coast, with Barranquilla teaming up with such nearby cities as Cartagena and Santa Marta – much as South Florida’s Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties often collaborate to attract investment.

“If we jointly promote Colombia’s Caribbean region, we can attract more attention and more business for us all,” says the triligual Osorio. She worked in investment promotion for varied entities from New York, Bogota, and Brazil but returned to Barranquilla two years ago to help her now transforming hometown.

Key to the future, leaders say, will be keeping up both the strong union between business and government and the long-term vision, sparked by Char and his peers. “Right now, we’re all aligned and working together for the city to progress,” says Osorio, proud of changes made since the 2000s. “What’s important is continuity of the private-public partnership for decades to come.”