Trade between the Miami Customs District and the world rose by more than $16 billion last year- and the future looks even brighter

By Yousra Benkirane

The past few years have been full of both challenges and opportunities impacting international trade. While the pandemic sped up certain trends that reimagined the future of the global economy, like the rapid expansion of digitalization, it also revealed our vulnerability to disruptions in the global supply chain – something the Miami Customs District is now well-aware of.

In the wake of the pandemic, trade took a substantial hit. In the second quarter of 2020, exports from the District – which includes all of South Florida – fell a whopping 32.2 percent, while imports dropped 28.3 percent. But the District quickly bounced back. In Q2 of the following year, exports grew 56.1 percent and imports rose 57.4 percent; another year later (2022), exports grew an additional 20.9 percent, with imports rising 17.6 percent, leading to optimism about a future that had been in doubt.

“The pandemic is something that should have hurt Florida the hardest, much like the global recession did in 2007,” says TJ Villamil, senior vice president of international trade & development at Enterprise Florida, the state’s commerce department. “Instead, we’ve seen the opposite effect take place, where Miami and the state are a lot more resilient than the rest of the country in the face of all the headwinds taking place around the world.”

Andy Hecker, assistant port director and CFO at PortMiami, says that cargo demand peaked to an all-time high in 2021, as home-bound consumers ordered record levels of products – something which helped snap supply chains across the world, especially those between Asia and the U.S.

Not surprisingly, last year’s post-pandemic cargo volumes were slightly down, due to everything from inflationary and interest rate pressures to an over-abundance of inventory from the previous year.

The positive news is that volumes fell less in South Florida than elsewhere in the U.S., and the dollar value of goods actually rose. At PortMiami, says Hecker, “volumes were a little soft, and for us, that is a seven or eight percent downturn after reaching an all-time high in 2021… other ports around the country saw a 10 to 18 percent softening, so we were a fraction of that.”

In 2022, total trade for the Miami Customs District was valued at $136.6 billion, compared to $120 billion in 2021 and $96.8 billion in 2020. The total for the District – which includes Miami International Airport (MIA), PortMiami, Port Everglades, Port of Key West, Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport, West Palm Beach International Airport, and Port of Palm Beach – represented more than two-thirds of all 2022 two-way trade for Florida, valued at $190 billion. And within the District, most merchandise was handled by MIA ($73.8B) and PortMiami ($32.9B), together more than half the state’s total.

STRONG NUMBERS, GOOD POSITION

According to Miami International Airport’s Marketing Division Chief Jimmy Nares, the last three years have seen the highest recorded cargo volumes for the airport. In 2021 specifically, MIA reached a new record of 2.75 million U.S. tons, a volume that remained consistent in 2022 while the dollar value rose.

The top commodities that go through the airport are flowers and pharmaceuticals, thanks to state-of-the-art cold storage facilities. In 2022, 90.5 percent of all U.S. flower air imports came through MIA. At the same time, the airport handled $7 billion worth of pharmaceuticals imports, another record-breaking achievement.

“There’s been a shift in trade all around the world,” says Nares. “While supply chain disruptions occurred for many different airports and markets, I think we were less impacted than most. We just continue to have a very strong logistics community that’s equipped and capable of handling perishable products. And we’ve benefited from that.”

At PortMiami, similar shifts in perishable commodities are taking place. Hector says that Greater Miami is poised to benefit from droughts affecting the U.S. Southwest, which “puts a lot of pressure on food grown in the U.S.” Rather than trucks rolling to Florida from Western U.S. agriculture, there will be more products arriving by ship from Central America and eastern Mexico. “This means new [ocean-bound] products coming into the U.S., refrigerated food products for the U.S. consumer, and that bodes very well for Miami,” says Hecker.

As another leader in handling perishables, Port Everglades has traditionally been well-connected to Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) sources. The port handles around 140,000 containers (TEUs) of perishable goods annually.

According to Director of Business Development Jorge Hernández, importers are gearing up for growth in cold storage so they can move more perishables like fruits and vegetables that come from Latin America and the Caribbean to Port Everglades.

In addition to handling big cargo lines like the Mediterranean shipping line MSC, Port Everglades also works with smaller carriers, like Seacor and HLS, which have more niche routes to and from places like the Bahamas or the Dominican Republic. This is “essentially their only way of bringing goods for consumption into [those] countries,” says Hernández. “These are not countries that produce much of the goods they consume on a regular basis.”

Indeed, connectivity with Latin America, Central America, and the Caribbean remains one of the strong suits of the Miami Customs District. Villamil compares Miami’s trade capabilities to international gateways like Singapore and Dubai, referencing its “perfect location between two continents in the Americas.”

VALUE ADDED

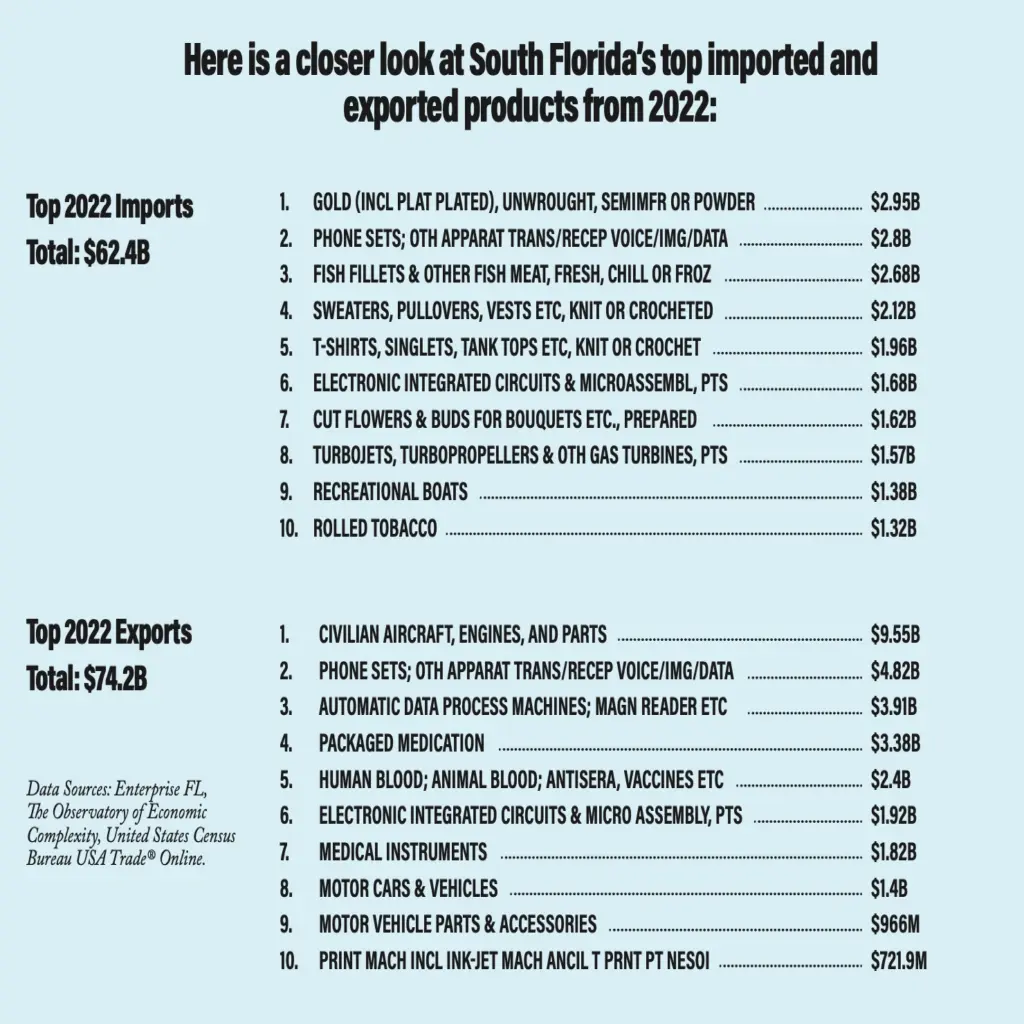

Manny Mencia, the newly instated chairman of the board of World Trade Center Miami and previous senior vice president of international trade and business development at Enterprise Florida, notes a key trend that has increased the value of the Miami District’s exports: the domination of high-value goods.

“The products that lead Miami exports are things like aviation and technology, medical-related exports… These are all high-end, high-tech, high-value exports, and Miami seems to be doing very well as an exporter of those products,” Mencia says.

Today, the top 10 commodities exported by the District are all high-value, whereas in the past Miami was known primarily for being an exporter of agricultural goods (think citrus). Essentially, Florida has diversified into new industries (something the pandemic accelerated), and as technology products are increasingly used in daily life across the globe, the District has become a top distributor of high-value merchandise like telephones ($4.82B) and computers ($3.91B).

Products like electronics are generally manufactured in China and then imported to Miami, which redistributes them to Latin America and the Caribbean. China is Miami’s top source of imports and third-largest trade partner overall, with bilateral trade totaling $8.57 billion in 2022, $7 billion of which was imports. Despite the overall drop in U.S. imports from China (down 13.3 percent for the first four months of 2023), the Asian country is one of Miami’s top two partners outside of Latin America and the Caribbean, the other being the UK ($4.89B total trade 2022).

Pushed by the recent supply chain issues, Florida’s trade experts are challenging businesses and the state itself to move away from China as a primary source. “This just shows how tied we are to the supply chain with China,” says Villamil, “As we divest from China, and we invest more in other developing economies, I think Florida is going to continue to thrive because we’re so well positioned.”

With supply chain weaknesses revealed by the pandemic, companies are now reassessing their sourcing of parts and raw materials, with Latin America and the Caribbean in mind. “We’d be better off having a lot of these products manufactured in Latin America and letting [Miami] do distribution domestically and internationally,” says Mencia.

Take, for example, Embraer, a Brazilian multinational aerospace manufacturer that has its North American headquarters in Fort Lauderdale. Embraer is the largest importer of aviation exports from Florida, where aviation and aerospace are leading industries (aviation merchandise is the District’s number one export by dollar value, at $9.5 billion last year). Embraer buys large numbers of aviation and aerospace components that are manufactured in Florida, sends them to Latin America to be assembled, and then returns them to the District as a finished product to be sold.

“We don’t think Asia is going away, but they certainly have some issues,” says PortMiami’s Hecker. “But what we do see happening is an increasing of nearshoring, shifting back to the western hemisphere. Some will shift but not all, so the phrase is ‘China plus one.’”

DIVERSIFICATION A MUST

Although our neighbors to the south are Miami’s biggest strength when it comes to trade, experts caution about putting all of the District’s eggs into one basket. With most of Miami’s top trade partners located in Latin America and the Caribbean, concerns about economic decline and instability in the region are encouraging businesses to expand into new economies. “Latin America is, and will always be, the line of least resistance,” says Mencia. “It’s our backyard, it’s our natural turf. However, when your markets are so oriented to one part of the world, you run into the risk of what happens when you have a regional downturn or even a market-specific downturn. You are liable to take a harder hit if you aren’t more diversified.”

Nares notes that while MIA handles 83 percent of all air imports and 80 percent of all air exports between the U.S. and the LAC region, the airport is now looking to add freight services to African markets and to Asian markets outside of China. Currently, there is only one freighter airline operating from Africa and just a handful from Asia, yet “these are areas that hold the greatest opportunities for us to grow,” says Nares. “Growing our global network outside of Latin America and the Caribbean poses the most opportunities for us.” The same advantages that position Miami as an Americas hub also present opportunities for businesses in Sub-Saharan Africa seeking to enter Western Hemisphere markets. Miami is the closest U.S. city to mainland West Africa, about 4,110 miles away from Dakar, Senegal. A nonstop flight would take approximately eight and a half hours. Although this connection does not yet exist, it presents a lucrative opportunity for airlines and investors who want to facilitate both passenger and cargo transportation between the two continents.

Likewise, says Hecker, PortMiami sees that “Africa is an opportunity and being on the East Coast of the U.S. gives us an advantage. We think that Africa is an untapped opportunity.” Enterprise Florida’s Villamil agrees: “As Sub-Saharan Africa grows, Florida is going to be poised to benefit, much like we benefited from the rise of South America and their economies.”

That’s not to say Miami should curtail trade with the LAC region – it is the District’s number one selling point, after all. “But I would love to see more of our European partners and sophisticated economies in Asia, like Japan, buy Florida products and services,” Villamil says.

In the meantime, Miami’s District is going to continue to see increased two-way trade with all the economies to the south. Brazil is Miami’s largest trading partner by far, accounting for nearly $17 billion out of the total $136 billion, with Chile, Colombia, Honduras, and the Dominican Republic all big contributors. “We recently started a new shipping line coming from Honduras, which is a business that wasn’t here before,” says Port Everglades’ Hernández. As for increased trade with Europe, both Hernández and PortMiami’s Hecker say that Florida’s pandemic-driven explosion in growth is attracting more trade by virtue of stronger domestic demand for goods from the continent. “What we continue to see is that, as the population in Florida continues to grow faster than the rest of the U.S., we continue to get more volumes across the board and more out of Europe,” says Hecker. “That is something that we are going to continue to see grow.”

THE NEXT CYCLE

So, what’s next? With new growth expected from nearshoring in LAC, new routes from Asia and Africa, and expanding trade with Europe, experts say capacity will be a key issue in the future. In the Miami Custom’s District, plans are afoot to deal with new demand.

Port Everglades is taking on initiatives like using new technology to be able to stack more containers on top of each other, freeing up land space. The port is also exploring alternatives with the Florida East Coast Railway to be able to use its intermodal container transfer facility more effectively, moving cargo more quickly. With limited land (surrounded by the city of Fort Lauderdale and its airport), “We have to think about how we densify the various cargo yards to be able to handle more cargo and to be able to provide space for new business opportunities,” says Hernández. “It doesn’t mean that there are no ways to expand, it just means that we have to think smarter.”

PortMiami, also landlocked, has focused on technology to accelerate services and therefore capacity without physical expansion (see story pg. 46). But it also has plans to create an inland facility in the Northwest corner of Miami-Dade County, linked by rail to the port, for the storage of TEUs and the location of other cargo facilities.

MIA, meanwhile, is working on adding more cargo infrastructure by building up rather than out, with a planned multi-billion dollar Vertically Integrated Cargo Community. “The biggest challenge in the next five or 10 years will be to have adequate infrastructure at the airport to be able to accommodate the growth that we’re seeing, and also the forecasted growth that we’re expecting in years to come,” says Nares.

Overall, with the right leadership, policies, and infrastructure, the Miami Customs District is well-positioned to expand its international trade capabilities. There may be unforeseen global disruptions that could slow down the rate of growth, but “fluctuations on the downside tend to be mitigated because we are [increasingly] balanced in all regions,” says Hecker. “Right now, we are looking at a re-setting of the market, getting ready for the next growth cycle.”

Trade by Product

Partners are one aspect of trade, volume another. But product type is key.

Taking a closer look at trade through the Miami Customs District, it becomes clear that each primary port has its own niche. Most high-value products, such as gold, electronics, and live animals, come through Miami International Airport. Most bulk products like fuel, agricultural products, heavy machinery, and automobiles come through Port Everglades and PortMiami.

PortMiami is known for handling containerized cargo carrying a diverse range of goods such as electronics, furniture, apparel, machinery, chemicals, and consumer goods – hence the nickname “Cargo Gateway of the Americas”. It serves as a major hub for international trade with the Caribbean, Latin America, and the Asia-Pacific regions. It is the largest container port in Florida and ninth in the United States. In 2022, PortMiami recorded $32.9B in total trade.

Port Everglades, located in Fort Lauderdale, has historically handled bulk products such as coal, minerals, grains, and other raw materials. It is a major entry point for petroleum products, including gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, and other refined petroleum products for both the local market and regional distribution. These commodities are typically transported in bulk carriers and serve different industries such as power generation, construction, and agriculture. The port is also growing its capacity to handle perishables and containers. In 2022, Port Everglades recorded $28.62B in total trade.

Miami International Airport is a major hub for perishable goods, particularly fruits, vegetables, flowers, and seafood, due to the need for temperature-controlled facilities and specialized handling to maintain freshness during transit. The airport plays a vital role in the transportation of pharmaceutical products and medical supplies, such as temperature-sensitive drugs and vaccines. The airport also handles cargo related to the aerospace industry, including aircraft parts, engines, and other aviation equipment, as well as high-tech and electronic components (mostly from China) to be redistributed to Latin America and the Caribbean. In 2022, the airport recorded $73.8B in total trade.