Miami International Airport’s ambitious $2 billion plan to expand its cargo facilities

By Kylie Wang

On November 30th, the ballroom at a Hilton hotel near Miami International Airport was buzzing. Hundreds of top trade officials from the airport, PortMiami, Enterprise Florida, American Airlines, World Trade Center Miami, and more were in attendance for the annual State of the Ports luncheon.

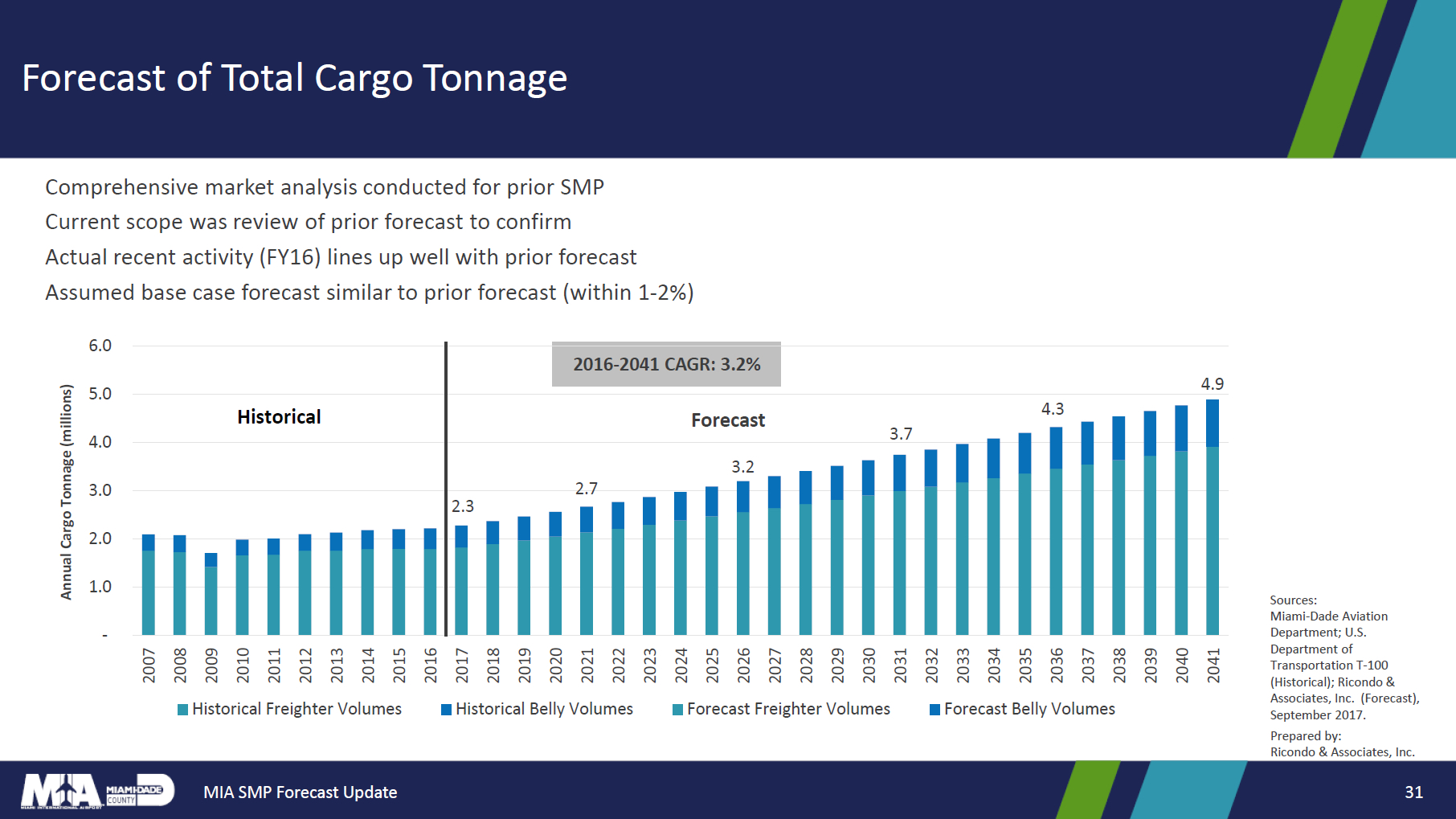

As Miami International Airport (MIA) director Ralph Cutié took the stage, there was no question that Miami’s airport had a record year in trade. It was the number one airport in the U.S. for international trade in 2022 and was on pace to set a record for total cargo moved (over 2.8 million tons) by year’s end. But there was a question about one aspect of the airport’s future. While cargo numbers had been steadily rising for the last few years, propelled in part by high demand during the pandemic, MIA was quickly topping out. Its full capacity was forecast to be reached by 2025, and an initial proposal for a new cargo facility had stalled in January 2022 after Miami-Dade County Mayor Daniella Levine-Cava had rejected it in favor of further negotiations.

It was a surprise, then, that Cutié announced the imminent approval of that same facility, MIA’s new $2 billion Vertically Integrated Cargo Community (VICC), a state-of-the-art facility that will double MIA’s cargo capacity and cement its position on the global stage.

CCR Group, one of the world’s leading investors in aviation infrastructure, and Airis, an aviation facility development company, had submitted the unsolicited proposal for the project to Miami-Dade County back in 2020. Negotiations between MIA and CCR+Airis were finally approved by the Board of County Commissioners (BCC) last March and since then have resolved most issues, with a few specifics still being finalized. Final approval by the BCC is expected in the first quarter of this year.

A PROJECT WHOSE TIME HAS COME

For the fastest-growing large U.S. airport, the VICC is now a necessity. In the last few years, MIA has experienced double-digit increases in cargo, and is expected to continue that pace in 2023. “Currently, we’re almost at capacity,” Cutié admitted during his State of the Ports speech. “This project will posit MIA as one of the premier cargo airports in the entire world. It will keep us competitive.”

In its proposal, CCR+Airis offered this assessment: “Cargo operations at MIA encompass 34.9 percent of the net operable airport land area today, however, it represents only 6.6 percent of total MIA revenues. This disparity… means MIA will begin to lose appreciable cargo volume to other competing airports sometime soon… along with thousands of associated jobs and associated economic benefit.” The VICC, with a projected $35.5 billion in economic benefit over its 50-year lease, would be the solution.

The five-story facility will be an uncommon sight in the U.S., where multistory cargo terminals are so far unheard of, but is actually modeled off of a similar concept at Hong Kong’s airport (HKIA), the world’s busiest international cargo airport. In 2021, HKIA’s facility was able to move five million tons of cargo, equal to what MIA could be moving upon completion of the VICC – although those numbers aren’t likely to be met until 2041, according to estimates by the airport.

“It used to be that the U.S. led the world in terms of aviation infrastructure,” says Ron Factor, Airis chairman and the VICC’s executive development officer, “but we lost that position after 9/11, understandably. Our airports are old… and their infrastructure is out of date. Most of the high-value, high-tech, time-sensitive materials are moved by air transport, but there’s very little accommodation in the U.S. network to handle that. Our quest is to bring the standards of our airports up… and regain leadership in this sector.”

The VICC will be a major step in that direction, expected to satisfy capacity demands for the next 25 years and bring the airport into a new era on the global stage. It should keep MIA’s cargo capacity from cresting until at least 2041 and will create more than 3,000 permanent cargo operations jobs (as well as almost 14,000 during construction), ensuring that MIA will remain the leading economic engine in Miami-Dade County and the state of Florida.

“It being the first facility of its kind in the country does put us on the world stage,” says Basil Binns, deputy director of the Miami-Dade Aviation Department. “It very well may be a prototype for how cargo development spaces are programmed in areas like Miami that have limited square footage and a limited footprint.”

CCR+Airis is already working on a similar proposal for a VICC to Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), another land-constrained aviation gateway. Both LAX and MIA require unique blueprints since the metropolitan airports have little space to expand – which is why the VICC is being built up rather than out. It’s an unusual, vertical take on the kind of single-story cargo processing facilities seen at large U.S. airports like MIA and LAX.

Of course, no two VICCs are the same, and Factor says the LAX VICC is still in the works while Miami’s “is years ahead.” The Miami VICC will also have a specific custom design to accommodate the movement of perishables, one of MIA’s main cargo functions, while the Los Angeles project’s design will focus more on moving the electronics and equipment that characterize trans-Pacific trade.

Even with other good candidates like LAX, Miami was CCR+Airis’ first pick, partly because of its current cargo growth and partly because “Miami has leadership that promotes commercial expansion,” according to Factor. Indeed, Cutié has embraced the project, telling GLOBAL MIAMI that the VICC is “a unique opportunity… to enhance our air cargo capacity and operations… as well as to leverage advanced technologies, develop high-efficiency facilities with e-commerce centers, and minimize our fixed costs.” What’s more – and a key element for county approval – the $2 billion price tag is being funded by the private sector, primarily by the CCR Group.

Of the five floors at the VICC, four will be dedicated to cargo processing. Automated facilities using robotic technology will take over the first two floors, while levels three and four will handle more “traditional” processing of cargo, according to Binns. The top floor will fulfill the last C in VICC – “community” – with amenities for workers ranging from restaurants to retail to even a potential daycare for employees’ children.

FINAL APPROVAL EXPECTED IN Q1

While final approval by the BCC is pending, the airport expects to receive the go-ahead in the next few months. “I wonder how much more we could accomplish if [our facilities] were more updated, if we were technology-ready, if we had the right kind of infrastructure we need,” said County Commissioner Jean Monestime, who recently finished his tenure. He and his colleagues were initially concerned that the VICC proposal needed “more vetting” before negotiations could be approved, but after several amendments to the proposal ensured that other planned projects near or in MIA would not be disrupted, those negotiations got the green light. Binns, who is the chief negotiator, agrees that one of the biggest challenges was how to relocate facilities on the land in the West Cargo Area that the VICC would take over. “Part of what we’re negotiating is those replacement facilities, whether they be temporary or permanent– permanent is our goal – for the displaced tenants,” he said.

The VICC is not the only private sector company trying to expand cargo capacity at MIA. Several operators, including FedEx and DHL Express, are already in the midst of, or have just completed, their own expansion. In 2021, FedEx added 138,000 square-feet to its main sorting facility at MIA, a $72.2 million project, and DHL Express invested $78 million to expand its hub, a move that will double its sorting capacity. Florida East Coast Railway and Atlas Air have also presented conceptual expansion plans for review to the airport. These efforts are not sufficient to handle demand, however, from myriad other cargo carriers. “We’re in a fortunate position right now where everyone wants to expand,” says Binns, “which is what makes the concept of a VICC so attractive.”

Besides allowing the airport to better utilize its current facilities, the VICC will also provide a sustainable model in aviation facility development. By consolidating cargo operations, the VICC will reduce CO2 emissions by 10,000 metric tons per year, largely by reducing emissions from trucks that currently must move between three separate cargo areas at the airport. Its solar panels will also generate as much as 3,600 MWh (megawatt hours) of clean energy annually.

Thanks to these and other sustainability initiatives, the VICC will receive a Gold certification from the Global Infrastructure Basel Foundation (GIB), a United Nations-backed nonprofit, making it the first aviation sector project in the Western Hemisphere to receive the designation. The GIB SuRe certification, which stands for Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure, is a global standard made to “drive the integration of sustainability and resilience aspects into infrastructure development.”

Construction is expected to begin early this year, immediately following final approval by the BCC.