Trade & logistics hub of the Caribbean

With unparallel economic growth for decades, the DR now strives to become the logistics center for the Caribbean, and a “nearshoring” powerhouse of the Americas

Sponsored by: AMCHAMDR and World Trade Center Miami

By Doreen Hemlock Photography By Rodolfo Benitez

First came agriculture, then manufacturing and next, tourism. Now, the fast-growing Dominican Republic, the Caribbean nation known for quality cigars, medical device exports, and all-inclusive resorts, is embarking on a new economic frontier: logistics.

Building on strong international air and sea links, the well-connected country has set a goal of becoming a regional logistics hub – to produce, store, and trans-ship goods for the United States, the Caribbean, Latin America, and even Europe. Key to the effort: A $200 million-plus investment at its busiest airport in Punta Cana, aimed to send more cargo in the belly of passenger planes.

This new frontier may sound ambitious, but the Dominican Republic has a remarkable track record. It’s the country with the strongest economic performance in Latin America and the Caribbean over the past 50 years, according to the World Bank. Growth has been averaging about 5 percent yearly for decades, as the nation has become a manufacturing center and the No. 1 tourist destination in the Caribbean. Foreign investment keeps flowing in, thanks to stability, tax incentives, and a capable workforce.

The timing is ideal for a logistics hub now, says Dominican warehouse and transport expert Alexander Schad. As tensions mount between the U.S. and China, more companies selling to U.S. consumers have been shifting production out of Asia and into the Americas in a trend called “nearshoring.” Manufacturing has grown so much in the Dominican Republic in recent years that many producers now keep their supplies and finished goods in local warehouses instead of U.S. facilities. Some even ship direct from Dominican factories to U.S. customers these days, using a “just-in-time” program, says Schad.

“The response time to the U.S. is shorter here, so you can make those shoes you need in size 8, in red, and get them within days, instead of the weeks it would take to ship from Asia,” says Schad, CEO of Frederic Schad, the largest Dominican logistics firm, employing 1,300 full and part-time staff – up about 40 percent in the past decade. “With quicker response times, you don’t lose sales.”

What’s more, tourism to the Dominican Republic keeps rising – hitting yet another record so far this year. That means more passenger planes are available to carry out exports like tropical fruits and electronics and to bring imports needed for new hotels, homes, offices, and industrial parks.

“The COVID-19 pandemic proved that you need logistics. The world is integrated and globalized, and people want things now, no matter what,” says Francesca Rainieri, chief financial officer at private Grupo Puntacana, which owns Punta Cana International Airport and is teaming up with Dubai’s DP World on the $200 million-plus investment. “And connectivity that’s close and direct reduces costs and time.”

The government and business community are united in the logistics push. President Luis Abinader, a data-driven economist and millionaire businessman who’s developed hotels and other ventures, is focused on modernization and efficiency to spur investment and grow the economy. His administration already has shifted customs documents online for 24/7 access, signed a new customs law to replace a decades-old one, and streamlined paperwork for investors, among other measures to help trade.

Customs Director Eduardo Sanz Lovaton, a business lawyer who left a top private law firm to join the administration in 2020, is working with ports to get cargo dispatched within 24 hours. He’s confident that as nearshoring and air freight grow, “we’ll be talking about logistics in the Dominican Republic next decade in the same way we talked about tourism 20 or 30 years back, as an important economic driver.”

Here’s a look at how this nation of 11 million people in the heart of the Caribbean became Latin America’s top economic performer, and at the economic pillars that support its plans to become a regional logistics hub, including connectivity, free-zone manufacturing, tourism, agriculture, and energy.

HOW THE DR FAST-TRACKED ITS ECONOMY

Ask executives how the Dominican Republic managed to outpace regional peers in economic growth over the past half-century, and most start with two words: democracy and stability. The country boasts uninterrupted democracy since the 1960s, with continuity in policy to attract foreign investment and increase exports. Protections for investors have been rising, says Bill Malamud, long-time executive vice president of the American Chamber of Commerce of the Dominican Republic, known as AmCham DR, one of the country’s largest and most respected business associations.

“There’s no political party radically left or right,” so government works consistently with business to build the economy long-term, says Boston-raised Malamud, who’s married to a Dominican. “And with the U.S. as the top trade partner and more than two million Dominicans in the U.S., it’s probably the most pro-U.S. country in Latin America.”

Government embraces business, partly because the Dominican state doesn’t control oil or mining resources that could give it outsized weight in the economy, says Maximo Vidal, the Dominican banker who has lead Citibank for the Dominican Republic and Haiti since 2005. The country imports its fuel, and even its large gold mine is being developed not by the state but by a private company, Canada’s Barrick Gold. “Here in the Dominican Republic, 80 to 85 percent of wealth is held by the private sector. We don’t have a PDVSA, Petrobras or Pemex,” says Vidal, referring to the state oil companies in Venezuela, Brazil, and Mexico that influence politics there. The Central Bank also acts independently, adding stability.

“I believe the Dominican Republic has the opportunity to double the size of our economy again in the next decade or so,” based on the strengths and new opportunities in logistics, tech, and other emerging sectors, says the veteran banker. “If we really want to do it, we can.”

CONNECTIVITY: THE KEY TO A REGIONAL LOGISTICS HUB

The Dominican Republic is well-located for trade. It’s a two-hour flight to Miami and many cities in Central America and northern South America, three or four days by ship to Miami and regional Latin American cities, and near the Panama Canal, allowing goods shipped from Asia to be unloaded and sent on to other ports.

But location is not enough to build a logistics hub. What’s needed are frequent flights and sailings, so shippers have options to get cargo in and out regularly and travelers have lots of transport options as well, according to Erik Alma, CEO and chairman of Haina International Terminals, known as HIT or Rio Haina Port. HIT is the country’s busiest multi-purpose seaport for cargo, from electronics and grains to heavy equipment and containerized freight.

Alma says the Dominican Republic has built up the necessary frequency in recent years, both at seaports and airports. “We have at least 30 shipping lines that call at HIT. Sixteen sailing options leave the port every week for the U.S., so you have this tremendous level of frequency and connectivity,” he says Alma, whose port next to Santo Domingo handles much of the freight for the nation’s industrial free-zones.

Punta Cana International Airport has so many flights – more than 500 per week – that it now ranks as the second busiest tourist airport in the greater Caribbean, trailing only Mexico’s Cancun. Last year, Punta Cana handled eight million-plus passengers in and out, with direct flights to 90 destinations across the Americas, Europe, and beyond.

In all, the Dominican Republic has eight international airports and 12 cargo seaports that together handle $30 billion-plus in trade annually. The two busiest seaports, Rio Haina Port and DP World Caucedo, have invested more than $400 million in recent years to expand and modernize, adding new cranes and inspection machines, for instance. While HIT focuses more on shorter routes, Caucedo mostly handles containers for longer-hauls, often trans-shipping freight arriving from Asia onto Europe.

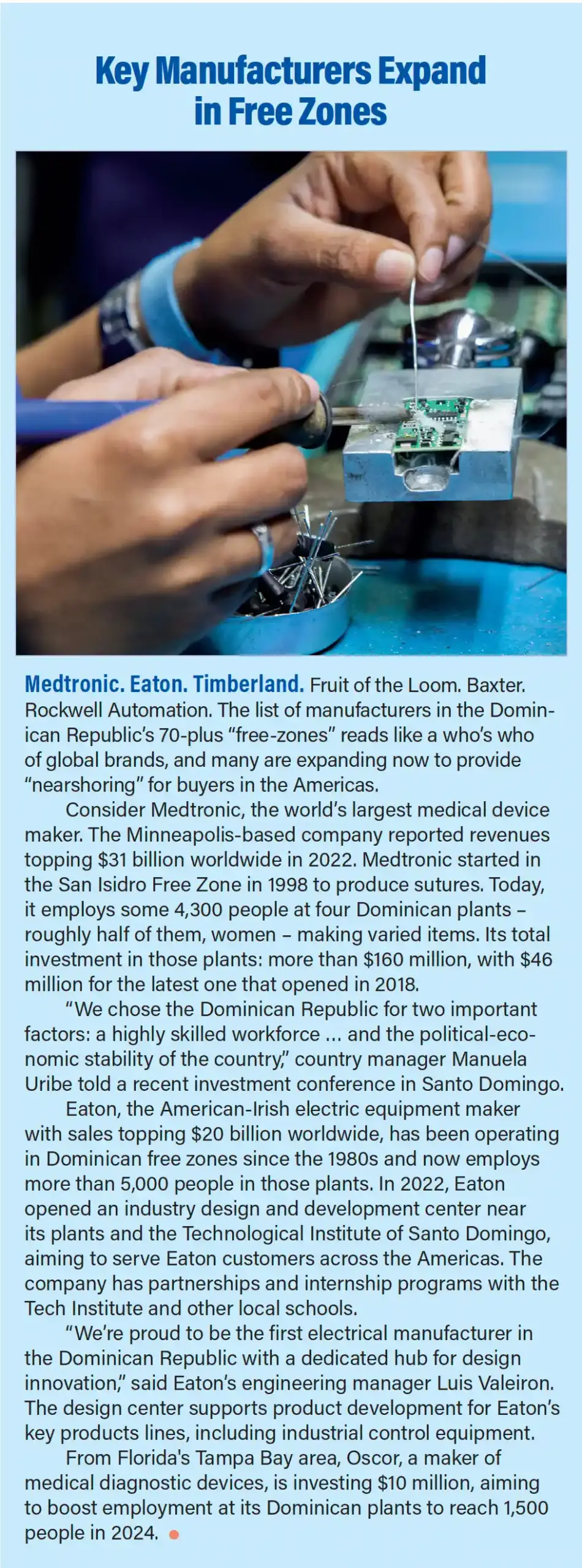

MANUFACTURING FOR EXPORT: A CATALYST FOR SEAPORT EXPANSION

Seaports developed their strong connectivity partly because of the boom in manufacturing for export in free zones, which offer exporters exemptions from import duties and taxes. The zones took off in the 1980s when their job count reached 100,000. Back then, most parks sewed clothes for U.S. sale, from Dockers to T-shirts.

Today, nearly 200,000 people work in 80-plus free zones nationwide, sending more than $7 billion in goods overseas yearly and providing such export services as modern call centers. Medical devices are the top export product, and even apparel makers in free zones have become more sophisticated.

HanesBrands, which started sewing operations in free zones in the 1980s, for example, built the largest textile mill in the Dominican Republic to produce some of its own fabric locally. It also dyes, cuts, and sews cloth to make garments, employing thousands of workers. Today, its fabric mill runs partly on biomass, such as coconut shells and wood remnants, reducing the need for fuel imports, says Jerry Cook, vice president of government and trade relations for the North Carolina-based apparel powerhouse which has global sales topping $7 billion a year.

“The Dominican Republic has done so many things right,” Cook says. “They’ve built out apparel and textiles as they developed other industries [rather than] phase out apparel as some countries have. And they’ve been very purposeful to work with industry to provide what we need, administration after administration… There’s an idea of growth for the long-term, built on government, business, and people as partner. And everyone is focused on the future.”

That evolution is clear at Zona Franca de las Americas, located near Santo Domingo’s international airport and the sprawling DP World Caucedo seaport. Las Americas launched in 1986 and initially produced mostly clothes and shoes for export. It now hosts 35 factories employing 21,000 workers, with many companies making medical supplies such as dialysis and intravenous kits. The Dominican Republic produces so many medical goods that it’s now set up a facility to sterilize those items locally. “We no longer need to send those medical devices overseas for sterilization, saving time and money,” says Las Americas Free Zone project manager Luis Manuel Pellerano.

Bela G. Szabo, the new CEO at Las Americas Free Zone, sees future opportunities in attracting both more suppliers of current manufacturers and expanding into new industries, especially in automotive parts like Mexico has. At least one Japanese auto supplier is now considering the Dominican Republic to make auto parts for U.S. sale, government officials said after a recent trip to Japan and South Korea that promoted nearshoring. The Las Americas Free Zone also is diversifying revenues by welcoming more tenants that offer services to factories, from finance to insurance, says Szabo. “We have a unique opportunity now in the Dominican

Republic after the pandemic and supply chain disruptions,” says Szabo. “By developing as a logistics hub, with more volume and connectivity, we can further cut transport and inventory costs, making us more competitive.”

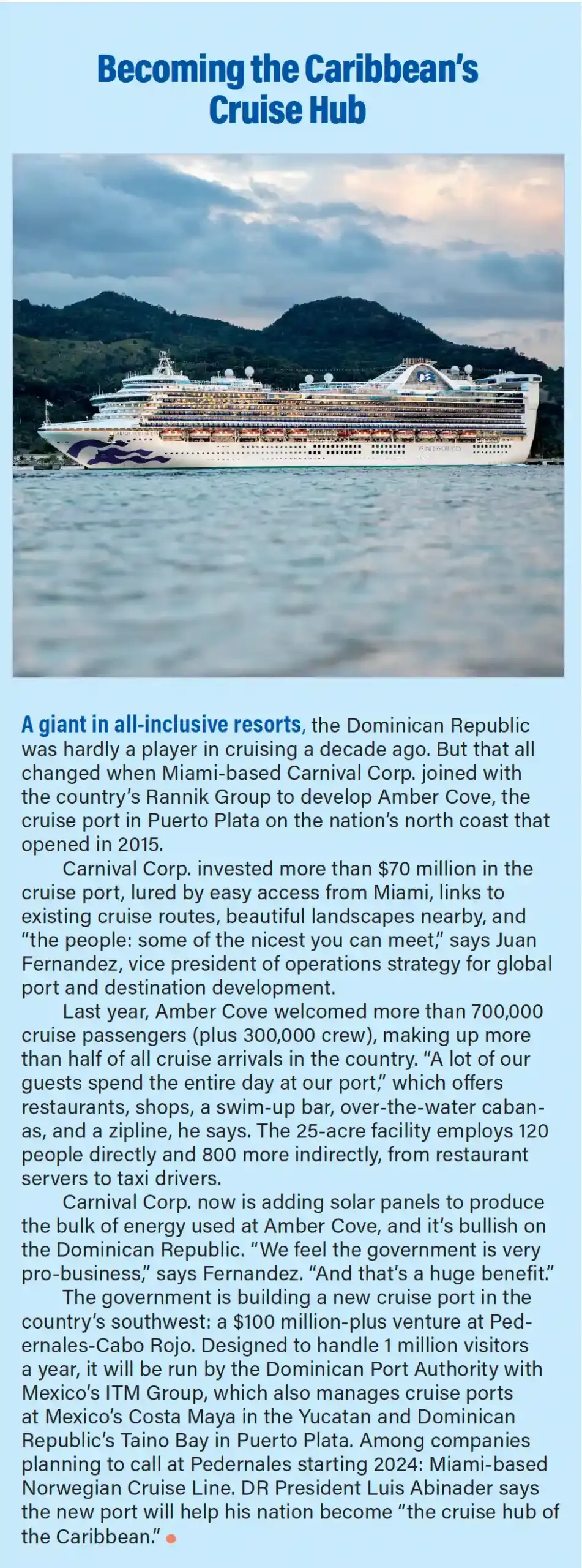

TOURISM: A PILLAR FOR LOGISTICS – AND SOARING

The logistics drive also is rooted in tourism, especially in booming Punta Cana, the nation’s tourism mecca. A half-century ago, Punta Cana was an undeveloped area considered remote from the capital city. In 1969, a private group of U.S. partners bought a large beachfront swath there, slightly larger than Manhattan. Joining with Dominican entrepreneur Frank Rainieri, the group welcomed Club Med as their first big resort in 1981 and opened their private airport in 1984, a move many called fool-hardy at the time.

“It’s the first international, private, commercial airport in the world, because no government wanted to put an airport in the middle of nowhere. And at that time the concept of concessions didn’t exist” for private companies to operate public-owned airports, explains CFO Francesca Rainieri, one of Frank’s children in the business.

Today, greater Punta Cana has nearly 50,000 hotel rooms for such brands as Spain’s Melia and Iberostar, and Florida’s Margaritaville and Hard Rock. That’s nearly as many as the 66,000 rooms in Miami-Dade County, an area that developed for tourism for twice as long. At least a dozen more hotels are planned in greater Punta Cana, including the country’s first W Hotel, an all-inclusive project by hotel giant Marriott in partnership with MAC Hotels and Grupo Puntacana. Opening for the 349-room W is set for 2025, part of Marriott’s push into luxury, all-inclusive resorts worldwide. Also expanding is Miami-based Karisma Hotels & Resorts, which operates three of its 23 properties worldwide in the Dominican Republic. Karisma owns Nickelodeon Hotels & Resorts Punta Cana, a luxury, all-inclusive complex for families, with 460 suites and a villa called the Pineapple, inspired by SpongeBob Square Pants’ home. It also runs Margaritaville Island Reserve Cap Cana’s two luxury, all-inclusives: Hammock for families and Waves for adults-only, together offering 500-plus rooms and 40 villas.

Karisma plans two more Dominican hotels, though details have not been released. “The biggest surprise of doing business in the Dominican Republic has been how friendly the government is to the hospitality industry. They have some fantastic programs that encourage investment and fuel the industry,” says Frank Maduro, president of Miami-based Premier Worldwide Marketing, the sales and marketing representative for Karisma. He suggests investors “lean on” government incentives to grow.

All those hotel rooms need air lift for guests, and that’s where the private Punta Cana International Airport comes in. About 15 years ago amid global recession, Grupo Puntacana began suggesting that passenger airlines add cargo to boost their revenues, taking out tropical fruits and flowers and bringing in needed hotel supplies. “It started because we wanted to make sure the airlines didn’t take away routes” in tough times for tourism, says CFO Rainieri.

Now, the group is taking that idea further by partnering with DP World to launch Punta Cana Free Trade Zone and Logistics Hub at the airport, an area that will provide space for warehouses, manufacturing, call centers, tech ventures, and even a maintenance operation for commercial jets. The plan is to handle not just cargo made in, or bound for, the Dominican Republic, but also to offer the airport’s connectivity to regional neighbors, likely flying out fruit and flowers from Colombia and Ecuador to the U.S. or Europe.

“We want to make this hub the most efficient, with the highest standards,” teaming with seaports for those shippers who want to combine more expensive, faster air links with slower, more affordable sea routes, says Rainieri. “We’re building on our business foundation step by step.”

Grupo Puntacana is stoking demand for freight too. It just bought land in Miches for two major resorts and plans several, ultra-luxury boutique hotels on its original property. For local workers, it’s building a community with 20,000 units of affordable housing “that we don’t make a penny on, in a social-responsibility project to ensure the area is sustainable and improves quality of life,” says Rainieri.

AGRICULTURE: EXPORTING NON-TRADITIONAL FRUITS

At airports and seaports nationwide, perishables are central to logistics. Long before tourism took off, agriculture sustained the economy, especially its “dessert” exports of sugar, coffee, tobacco, and cacao. The country remains one of the world’s top exporters of premium cigars ($1 billion-plus yearly), but agriculture has shifted more toward non-traditional fruits for export, such as avocados and papayas sold in the U.S., Canada, Europe, and beyond.

“Non-traditional agriculture really expanded with the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA) with the United States,” says Malamud of the AmCham-DR. That accord that took effect in 2007 and eliminated most duties on Dominican sales to the U.S. market. “Avocados, tomatoes, cucumbers, mangoes – anything you can grow in a greenhouse – the country now produces for export,” he says. Dominican sales got an indirect boost too, when the U.S. government provided technical assistance to help develop refrigerated capabilities known as “cold-chain” to facilitate farm exports to U.S. consumers.

The Dominican Republic has trade accords similar to DR-CAFTA with some 50 nations, including in the European Union, the United Kingdom, and in the Caribbean Community, easing sales of local goods abroad, says ProDominicana, the government’s organization to promote exports and investments. Under President Abinader, the agency is looking beyond helping individual companies and instead promoting a broader portfolio at trade shows.

“With our new strategic approach, we center our efforts on understanding how we can improve services that the country offers investors. We’re looking to expedite processes, avoid duplicate procedures, and offer greater security in regulatory matters,” says ProDominicana Director Biviana Riveiro, a business attorney. That approach helped launch the new One-Stop Investment Window and online registration for investments, among other initiatives for agriculture and industry, she says. The country also touts improving infrastructure, from solar energy parks and high-speed internet to new highways and Santo Domingo’s expanding subway network.

CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS

To be sure, there are hurdles to becoming a regional logistics hub, such as staffing. Business leaders see weakness in Dominican public education, including English-language skills. There’s already a need for more logistics specialists, sparking this year’s launch of a National Institute of Port and Logistics Training, says HIT chief Alma.

As the logistic hubs evolve and more Dominican factories enter e-commerce chains with the U.S., “the challenge is to do quick-turn business and build out the logistics model,” enhancing digital links and information flows, adds HanesBrands’ Cook.

Regional competition also abounds. Yet logistics specialist Schad sees a clear advantage for the Dominican Republic over its neighbors: market size. No other Caribbean or Central American neighbor has the critical mass of 11 million residents, 8 million-plus tourists yearly, and 80-plus free-zones producing exports. “And what’s behind our strong, growing market is Dominican joy,” says Schad, “a positive attitude and smiles that attract not only tourists but investors.”

Grupo Puntacana’s Rainieri points to the COVID-19 pandemic as an example of how the country meets challenges. Thanks to aggressive vaccinations, safety protocols, and strong public-private cooperation, the Dominican Republic was among the first to re-open to tourism in 2020 and quickly set new records for passenger arrivals, earning recognition from the World Tourism Organization. “The Dominican people are resilient. We’re looking for solutions,” says Rainieri. “And we’re in our best moment now, because everyone is aligned and working together to help grow and develop the country,” with logistics as the latest international frontier.