Saif Ishoof and the quest to create a global technology hub

It is a Thursday evening in September, and a group of about 150 people from the world of high-tech Miami – entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, software engineers, government officials, programmers, educators – have assembled on the 16th floor of the Padron building of Miami-Dade College. Unlike the cluster of downtown Miami skyscrapers in the distance, which sparkle as the sun sets, the Padron building is the only high-rise in its neighborhood of Little Havana. So, its views are unrivaled in every direction.

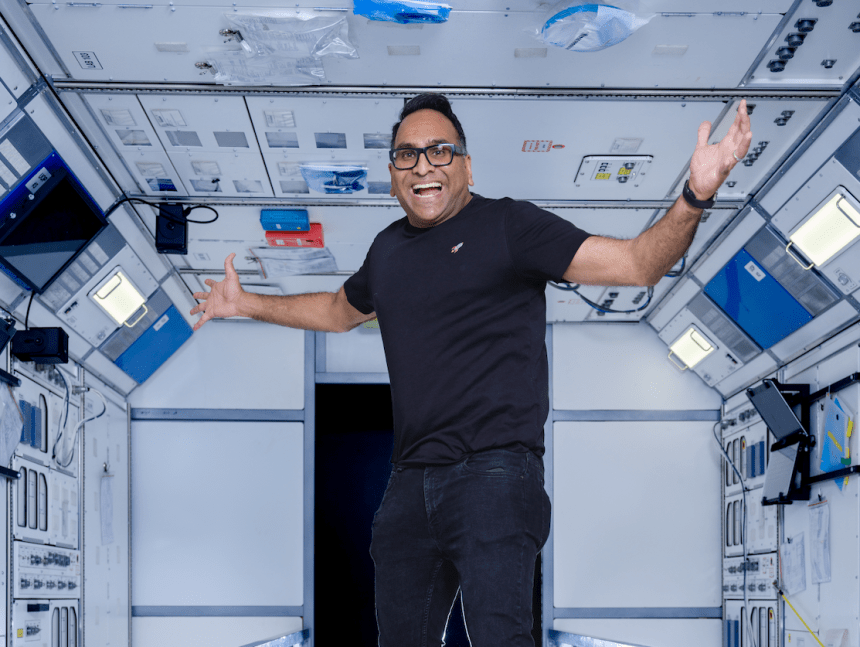

It is a fitting platform for the speaker and host of the night, Saif Ishoof, the humble but ebullient proselytizer for the vision of a New Miami, a city of technological innovation and aspiration, where ideas can blossom in a DNA of opportunity. The evening’s event is the third annual Moonshot Awards, honoring various South Florida leaders in innovation.

Almost everybody in the room has been touched by Saif (which rhymes with “life”), who has by serendipity and quiet persistence become what sociologist Malcolm Gladwell would call a connector – individuals who change the world by spreading ideas and trends through a wide social network of strategically placed people. The guests range from young inventors with startups to seasoned founders of billion-dollar corporations. The head of innovation for eMerge Americas is there, as is the head of the federal agency for small business acceleration, the co-manager of the Miami office for the billion-dollar managed asset fund Blackstone, and the Miami executive for global investment management firm Milenium. All of them know Saif, and many are in Miami because of him and the connectivity he has applied to Miami’s burgeoning tech scene.

The lead winner for the evening is Exowatt, a company that Saif ’s consulting firm Lab22c – the host of the Moonshot event– helped integrate into the Miami tech ecosystem. Exowatt won the Moonshot Award for developing a revolutionary approach to collecting solar energy, a modular system that uses a heat battery to store and dispatch power throughout the day, unlike traditional solar panels that convert sunlight directly into electricity. In April, Exowatt received a $20 million seed round from Miami-based venture funds a16z and Atomic, and OpenAI’s Sam Altman.

The second winner of the night was John Wensveen, who won the eMerge Americas Convener Award. Wensveen was, until just recently, the Chief Innovation Officer at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, and executive director of its Levan Center for Innovation, which has launched 200 South Florida startups through its incubator programs. Wensveen accepted the award in a live stream from Strasbourg, France, where he is now president of the International Space University. Wensveen met Saif nine years ago when he was new to Miami and just starting as Vice Provost at Miami Dade College. They met through Miami’s Academic Leaders Council, “and that’s how we became connected,” he told Global Miami Magazine. “We became pretty much instant friends because we had similar goals of where we thought Miami could go… It’s the Saifs of the world that are really creating awareness….”

The evening’s third winner was for the Artemis Award: Chester Ng, one of the co-directors of Atomic, a venture fund now based in Miami and San Francisco that invests in companies they build from the ground up. Ng’s partner and company founder Jack Abraham was “patient zero of the Miami migration, because he landed in the summer of 2020, in the heart of the pandemic, and never went back to San Francisco” where the company was founded.

“I was originally introduced to Saif by Mayor Suarez, when the mayor famously opened up his direct messages [‘How can I help?’] on Twitter,” Ng told Global Miami Magazine. “My wife and I were kind of half-seriously considering the move here, so we visited in April 2021…. [the mayor] introduced me to Saif who quickly invited me to have coffee in Coconut Grove, at Panther Coffee, and we walked and talked. And he was instantly, you know, just incredibly helpful and insightful.”

Saif ended the evening with one of his trademark odes, that building the technology ecosystem in Miami is entirely about collaboration. “For me, it’s an underlying sense that we all have a responsibility to try to bridge meaningful connections between people who are in pursuit of common cause or impact.” And that common cause: to make Miami a global center for technology and innovation.

THE MAKING OF A TECH CONNECTOR IN MIAMI

Saif Ishoof ’s tale is one of those quintessential stories about the Miami melting pot. Born in Guyana, his family moved to Miami when he was two years old. His father had a business that managed agriculture services for sugar and rice in Central America and the Caribbean, and Saif worked for the company after studying at the Georgetown School of Foreign Service in Washington, DC. After a year at the family firm, he then attended law school at the University of Miami but found it was not his calling.

“I was always fascinated by technology, specifically software,” says Saif. “So, when I was in law school, I started to dream up this idea for a company that would service agricultural businesses like the ones my dad worked with. I started the company as soon as I graduated.” His firm, located near UM, was an early vendor management software company. “That was my first foray into being an entrepreneur at the at the age of 24 and 25.”

Saif sold his software system to one of his largest clients and went back into the family business for a few years. But he remained, he says, “embedded in Miami’s innovation ecosystem.” Those were very early days for South Florida’s tech economy, consisting mostly of the remnants of the IBM campus in Boca Raton and Motorola’s campus in Broward County, as well as a handful of Latin American-focused tech companies. “The Miami ecosystem was very small, and I knew a lot of the players,” says Saif.

Feeling “a call to service,” Saif was then hired as the executive director of an education non-profit called City Year Miami, a domestic version of the Peace Corps focusing on the high school dropout crisis. Miami Realtor Tere Blanca, who was finishing her stint as chair of the Beacon Council at the time, recalls meeting Saif the evening when she passed the baton to the new chair. “As the program ended and I was walking out of the auditorium, Saif was waiting at the door. He said, ‘Miss Blanca, you don’t know who I am, but my name is Saif Ishoof, and I’m waiting for you because you’re going to be the next chair of the board of City Year Miami.’ I said, ‘Young man, you’re right, I don’t know who you are. And I don’t know anything about City Year Miami, but I have a feeling I’m going to learn.’” Six months later, says Blanca, “I joined the board and then became chair, and to this day, I continue to support the program.”

That was in 2010, and Blanca remains a steadfast Saif fan. “He has great vision for a lot of different opportunities ahead of us in our community, and is a very effective networker,” she says. “He’s doing a great job promoting not only the tech ecosystem, but also our region, and Miami in particular, as a place where entrepreneurs can succeed.”

After six years at City Year Miami, Saif became Vice President of Engagement at FIU, which gave him experience coordinating public-private partnerships and working to develop what he calls “the human capital ecosystem.”

Then the pandemic hit, and corporations of all types, including tech founders and investors, started moving to Miami, following Mayor Suarez’s “How can I help?” tweet to Silicon Valley. “Mayor Suarez called and said, ‘Would you be interested in playing a support role? Because we’re getting all these companies and investors that are moving here,’” Saif recalls. FIU and the city created a partnership that “lent” him as an advisor to the mayor; he quickly co-created Venture Miami, a city economic development agency to help relocate tech companies.

After a year with the city, Saif went back to the private sector and launched Lab22c (which stands for Laboratory for the 22nd Century), a management consultancy for tech firms, where for the last three years he has become the Miami technology’s ecosystem Connector in Chief. As such he is constantly in motion, a peripatetic proselytizer for the new Miami.

“He covers more ground in a day than most people do in a month,” says Caryn Lavernia, vice president and senior partner at Lab22c and a member of Saif ‘s team for over 16 years. “On any given day, he’s doing a mix of community events. So, he’ll go to a chamber [of commerce] breakfast, and then to an Orange Bowl committee lunch. All meals are kind of in community, and then he’s meeting with our clients,” she says. “Sometimes that is a one-to-one mentorship with a founder, or it’s introducing a client to a prospective partner.”

Saif also has a reputation for never saying no to people looking for advice. “Let’s say it’s a student he worked with at FIU eight years ago who needs a little bit of mentorship time. He always says yes,” says Lavernia, which can sometimes make scheduling Saif problematic. “So, it’s a total mixed bag. And then, of course, his family life is critically important to him, so he somehow finds a way to meld work life and the family life.”

Part of Saif ’s monthly routine includes two networking events. One starts at happy hour on the first Tuesday of each month, in the courtyard of Bougainvillea’s Old Florida Tavern in South Miami, and the other, a breakfast gathering on the second Tuesday of each month at Chug’s Diner in Coconut Grove. At either one you will run across participants ranging from UM coding students to software engineers to lawyers doing IPOs for new companies to representatives from foreign tech firms looking to make connections. His reach spans across diverse sectors, right up to billionaire Ken Griffin, CEO of asset manager Citadel. “Saif ‘s background in the public and private sectors has positioned him to serve as a trusted advisor for business leaders across Miami and Florida. His insights and commitment to our great city have been instrumental to its continued assent as a global hub for business and innovation.”

HOW MIAMI MEASURES UP IN THE TECH WORLD

Even with Saif ’s perpetual promotion of Miami and the incredible post-pandemic influx of new companies here, most pundits will tell you the city still has a long way to go. “Yes, Miami is a global tech hub,” says Tatiana Nascimento Silva, Chief Development Officer at the Beacon Council. “Just not in the top three – but on its way to break into the top 10. Miami has grown at an incredible rate, with Blackstone, Citadel, Kaseya, LeverX and Blockchain.com being some of the names that have moved here. And the data backs it up.”

One recent study cited by Silva is by StartUp Genome, placing Miami as the No. 16 Startup Ecosystem globally, and No. 6 in North America, ahead of Chicago, Seattle and San Diego. Coworking Mag, which publishes a ranking each year for the Top Ten [US] Cities for Startups, placed Miami at No.8 for 2024. San Francisco, New York and L.A. came in at the top, followed by Seattle, Chicago, Atlanta, and Austin. At No. 8, Miami did beat Denver and Boston, so not too shabby.

You can also look at how much venture capital is invested each year. The annual eMerge Insights report on 2023 shows that $2.4 billion was invested in the South Florida startup ecosystem across 393 deals, South Florida being defined as the Greater Miami-Fort Lauderdale area. That places the Miami-Ft Lauderdale metro region at No. 7 nationwide for number of deals, and 11th for deal valuation.

“The data is showing us that we are now in the global scene of tech ecosystems,” says Melissa Medina, the CEO of eMerge Americas. “That is a fact. We are seeing it also as an acceleration of South Florida post-Covid, how that affected the growth of technology with talent migration and tech companies [relocating] that weren’t here before – plus the capital elements. We are in the early phase of the Miami Tech Global Era. We just need a lot more of everything we have.”

Another measure is for pre-seed funding rounds. According to data research firm Carta, for the first 30 weeks of 2024, Miami ranked No. 6 in the U.S., ahead of Austin and Chicago, though still well behind cities such as San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles and Boston. For 2024, that represents $155 million, or about 10 percent of the $1.5 billion the Bay Area attracted – up from under 1 percent pre-2020. Seattle at No. 5, for comparison, came in at $163 million.

Employment is another way to gauge the metrics of Miami. According to research conducted at Florida International University, STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) jobs in Miami-Dade County alone reached nearly 48,000 this year. While that is a far cry from 330,000 such jobs in the Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim metro area of California, it represents an 18+ percent rise since 2019, compared to growth of under five percent in L.A., “We are an evolving tech community,” says Dr. Maria Ilcheva, the research professor at FIU who conducted the study. “We are not there yet but we are certainly heading in that direction.”

SOUTH FLORIDA TECH COMPANIES

What South Florida needs are more companies in the tech “space,” says Dr. Ilcheva, to achieve the critical mass needed to make tech growth “inherently sustainable and exponential.” And indeed, South Florida is now attracting a bevy of high-tech companies. Some, like Blackstone and Kaseya, are major players with large rosters of employees. Others plant just the company HQs, with production and admin offices elsewhere. Exemplary of this trend is Delian Asparouhov, the founder of Varda Space Industries. The mission of Varda Space is to produce pharmaceuticals in zero gravity, something Varda does with Space X rocket ships launching lab gear from a site in Utah. He is also a partner of Founders Fund, a $750 million venture fund based in California.

Asparouhov is notable as the Silicon Valley entrepreneur who issued the infamous tweet in December of 2020, “ok guys hear me out, what if we move silicon valley to miami” which engendered the “how can I help?” response from Mayor Saurez. In a more recent tweet this summer, Asparouhov posted “Excited to be back in Miami. It represents optimism, accelerationism & an appreciation of the American Dream in a way that no other city in the US does. We’re 3 years into a multi decade journey of making it the largest tech hub in the world. A strong start but much lies ahead.”

Asparouhov says Miami’s progress to date is nothing short of stunning. “Los Angeles has had Snapchat, SpaceX, etc., since the mid-2000s so [their ecosystem] is like 20 years old. Boston’s ecosystem is like 50 years old. Seattle, too, has an ecosystem 50 years old,” he says. “Miami did not really have much of an ecosystem until five years ago. So, I think it’s super exciting to see a place that did not have some super rich history as a startup and venture ecosystem to go from zero to sixth place [for startup funding] in the United States. It’s extremely promising, especially since it’s ahead of places like Austin, Chicago, and Denver, which have had startup ecosystems for 20-plus years.”

Similar to Asparouhov’s move is the HQ relocation to Miami by LeverX, a Silicon Valley enterprise software company with 1,600 employees in nine countries. Dr. Victor Lozinski, its co-founder and CEO, said he relocated to Miami in January of 2023 for key reasons. “Silicon Valley, where we started LeverX, is an excellent place where you can start a company,” he says. “But if you are trying to build an international company, with international operations, it’s getting more and more difficult, especially if you want to do a lot of work with Europe – because you will find a nine-hour time difference [and that] flying from Europe to California is almost like flying to the moon.”The majority of LeverX’s customers are also located on the East Coast.

Lozinski said he looked at locating LeverX’s headquarters in Boston or Philadelphia but found their airports inconvenient and not as well connected as Miami International. “We have this joke at LeverX, that if you cannot fly directly from any city in Europe to Miami, that means it’s not a city.” This year LeverX held their annual customer conference in Miami, a three-day summit called Leveredge 2024. “In the two years here, I have not had a single person telling me they will not come to Miami. Miami has this kind of magic.”

THE HISTORIC ROOTS—A HISTORY OF MIAMI’S TECH SCENE

In tandem with his Moonshot awards, Saif likes to break down the history of Miami’s technology evolution into the same phases as the U.S. space program. Part one was the Project Mercury phase of the 1990s, when Miami was recognized as the Gateway to the Americas and Latin “carbon copies” of U.S. internet and software companies appeared – an eBay for Latin America, for example. The second phase, from 2000 to 2010, Saif calls the Gemini era, when graduates from area universities stopped leaving South Florida and began setting up companies here.

Exemplary of this era was Rony Abovitz, an entrepreneur who studied bioengineering at UM and then, in 2004, founded Mako, one of the first manufacturers of medical robotic technology. He sold Mako ten years later for $1.6 billion and went on to start Magic Leap, a pioneering producer of virtual reality headsets (tested by students at UM). Both Mako and Magic Leap continue to manufacture in Broward County.

“When I built my first company, there was like zero [technology] scene here. It was like an anti-scene,” says Abovitz. “So, to build Mako Surgical in Florida was the antithesis of everything. Every investor told me don’t do it. No one wanted to fund us.” In the end, Abovitz convinced investors from California to believe he could build a company here. “I could have gone elsewhere but I just wanted to be a contrarian,” he says. His companies, with substantial employment rosters, helped spawn other startups by engineers who worked at them.

Next, says Saif, came South Florida’s Apollo era from 2010 to 2020, reflecting NASA’s massive program that finally put a man on the moon. This was Miami’s time of big players, when entrepreneur Manny Medina sold data company Terremark to Verizon for $1.4 billion (2011) then went on to found eMerge Americas (2014) and network security giant Cyxtera Technologies (2017). It was also when the Knight Foundation started funding innovations, when the University of Miami started its Launch Pad incubator, and when FIU created Startup FIU. It was a time when co-working spaces like Lab Miami started in Wynwood.

And then there is the era of now, what Saif calls the Artemis era, analogous to NASA’s declared program of returning to the moon and beyond. This is the post-pandemic era, ushering in what Saif calls “the decentralization of American innovation,” when companies began to relocate in droves from Silicon Valley, New York, Boston, etc. to Miami.

DEEPER ROOTS, WIDER BRANCHES—THE GROWTH OF MIAMI’S TECH SCENE

With the recent migration of startups and venture funds to Miami, it might seem like the South Florida technology ecosystem emerged overnight. But those with longer memories disagree. David Coddington, the Senior Vice President of the Greater Fort Lauderdale Alliance, was one of the founders of the Florida Tech Gateway, an organization promoting the South Florida tri-county area as a powerhouse of technology. Coddington will be the first to remind you that South Florida has a long history of technological innovations, including the IBM campus in Palm Beach County where the personal computer was invented and the Motorola campus in Broward County was the cell phone was invented. Both corporations have since left the area, attracted by incentives from other states, but their imprimatur created a pool of professionals that went on to start or join other firms.

Florida Tech Gateway is also known for creating the TechGateway Map, which shows the approximate location of 90+ South Florida companies that provide 116,000+ Information Technology jobs in South Florida. Employers range from Fort Lauderdale-based Citrix Systems, with 657 employees here (6,000 worldwide), to Weston-based Ultimate Software, with 1,650 employees here (5,000 worldwide).

“You know, Microsoft’s Latin American headquarters have been in Fort Lauderdale for 20 years,” says Coddington. “Another one is American Express. Their Latin HQ and their high-end customer service is out in Sunrise. They’ve got 4,000 people in that building… Probably Miami’s largest [tech firm] is Kaseya, and they are talking about 3,500 people.”

Tri-county technology companies reach all the way to the northern edge of Palm Beach County, where a life-sciences cluster has formed around the Max Plank Institute and where Florida Power & Light maintains its 35 Mules incubator. Boca Raton, on the south end of Palm Beach County, is home to firms like ADT and Modernizing Medicine, as well as the Research Park at Florida Atlantic University, which houses not only fully operational tech companies but also student incubator spaces and its Global Ventures program, founded in 2020 to help foreign companies locate operations in South Florida.

“Right now, we’ve got about a dozen different countries represented by 34 companies [in Global Ventures], and they are creating dozens of jobs,” says Andrew Duffell, CEO of the FAU Research Park. Located on 70 acres, the Park is a private-public partnership launched by Palm Beach County in the 1980s to help create jobs. “We’ve got 20 companies in the park itself,” says Duffell. “Many of them are multi-million-dollar enterprises, and a couple of them employ more than 200 people.”

THE EDUCATION MATRIX AND THE FUTURE OF MIAMI’S TECH SCENE

One of the projects Lab22c recently helped launch was a Rapid Innovation Accelerator in partnership with MoveAmerica and the Department of Defense. Announced at Miami Dade College’s downtown Artificial Intelligence Center, the idea of the accelerator is to link the huge purchasing power of the U.S. Military to innovative small-business suppliers in Miami. Saif, whose company will serve as the local operating partner, was the master of ceremonies. “At the end of the day, we know that venture capital is great,” he told an audience and panel that included Gen. Laura J. Richardson, commander of the Miami-based U.S. Southern Command. “But how about non-diluted capital that comes from a customer that happens to be the best customer you could ever want, the U.S. government?”

Saif ’s connection with MDC, in addition to FIU, is another spoke in the wheel of South Florida’s evolving ecosystem. Without a substantial flow of trained workers, Miami will never attain its potential as a global tech hub, something Saif is painfully aware of. To advance that agenda, Lab22c has worked for years with MDC, itself a forward-thinking educational institution. The school recently announced, for example, its new master’s program in AI, the first of its kind in the state. They also train corporate employees in Miami with modular programs in specific areas, such as coding, software applications, and AI, to bring them up to speed.

“I’m really impressed by the constant flux of new ideas, fresh ideas, that I’m seeing across various disciplines,” says Pamela Fuertes, the dean of MDC’s Miguel B. Fernandez School of Global Business, Trade and Transportation. “A lot of companies are investing here, and I see it in our student body and in our faculty.” Fuertes points to a new President’s Innovation Fund created by MDC president Madeline Pumariega, herself a relentless advocate of advanced technology curriculum, to fund innovative ideas by MDC faculty. “It provides resources for faculty who design new programs or design a new project with students,” says Fuertes. “It’s fascinating to see how far some of these projects go.”

Reflecting the school’s commitment to train students in advanced technologies is the role played by Antonio Delgado, MDC’s Vice President of Innovation and Tech Partnerships. In 2022 Delgado applied for and secured a $10 million federal Miami Tech Works grant that has been distributed to MDC, FIU, and Florida Memorial University to develop industry-led tech training. Lab22c, not surprisingly, is involved as the facilitator of the partnership of employers, academic institutions, and community organizations.

“What are the metrics that we need to continue growing as an ecosystem? One of the most important is talent,” says Delgado. “My role is to make sure that we have that tech talent, and that we train our community with skills that are relevant for our tech ecosystem, and for those companies either growing or moving to Miami.”

In this vein, MDC collaborates with corporations such as Microsoft, Amazon, Intel, Google, and Apple to make sure the curriculum is appropriate. “We follow trends to understand what we’re supposed to be teaching. That’s why we teach Java as the foundation for computer science because that’s what companies are looking for.” MDC is collaborating with Apple, for example, to train students in the use of the Swift programming language for iOS app development, needed to develop apps for Apple devices.

“To scale further,” says Jaret Davis, managing partner of Miami’s largest law firm, Greenberg Traurig, “Miami needs to continue to successfully recruit sources of capital along the entire fundraising life cycle – from Seed to Series A, to Series B, to growth equity and beyond. [But] Miami’s educational institutions also must continue to focus on producing top developers, data scientists, and similar talent. This includes significant collaboration with the local and external technology companies who will be the ultimate home to this tech talent.”

Davis also makes the point that every tech system needs to have leaders “who can appreciate both the macro picture of what is trying to be accomplished while having the vision, connectivity, and leadership skills to bring together local leaders and players, while also recruiting new entrants to implement that vision. That’s the role Saif plays.”

“Saif is like my brother from another mother. That is how long I have known him, maybe 20 years,” says eMerge’s Medina. “If there is one person who I would call the connector in chief, that’s Saif, and anyone who knows him would agree. He always thinks of how we can make the community more innovative, more knowledge-based, more forward-thinking, and more connected with each other.”

As Miami’s Connector-in-Chief, Saif puts it this way: “It brings me great joy to see good people come together. I’ve got this cheesy statement that I say sometimes, which is this: If I tell you what I am working on, you will want to compete with me. But if I tell you who I’m working with, you will want to collaborate with me.”